When Anastasia Holovko talks about her work as a regional monitor with Right to Protection (R2P), a Ukrainian refugee organization launched by HIAS in 2014, she distills its essence into a single word: listening. Working out of Chernivtsi, a city near the Romanian border, the 41-year-old Holovko spends her days helping displaced Ukrainians cope with assorted problems caused by Russia’s invasion of their country last February.

Some of these problems are practical, such as helping Ukrainians replace documents they lost while fleeing their homes. Other problems are less tangible but equally daunting: trauma, mental health problems, and recovering from gender-based violence.

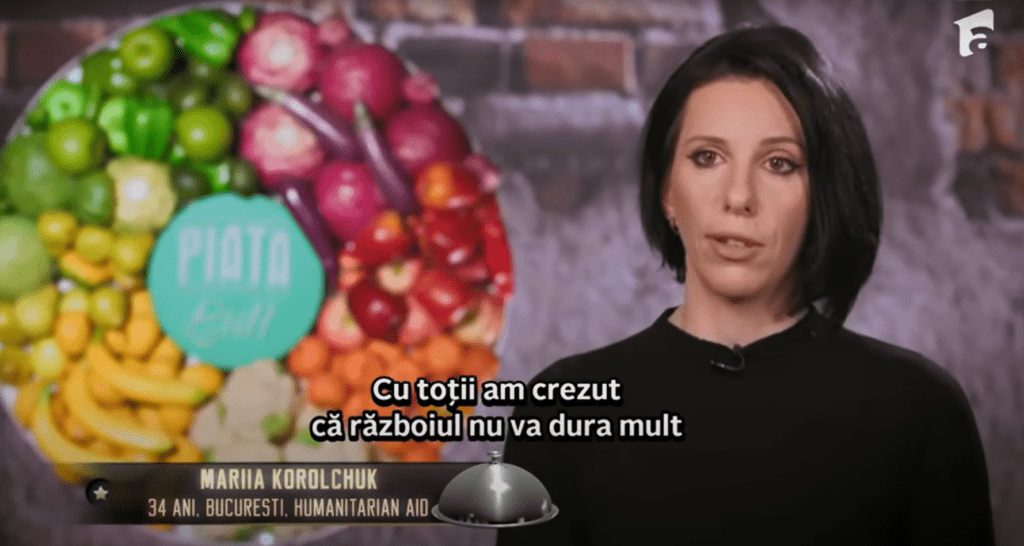

Anastasia Holovko, 41, shown at her job as a regional manager for HIAS partner Right to Protection in Chernivtsi, Ukraine. (Right to Protection)

Holovko isn’t a career social worker, lawyer, or mental health professional. Until last winter, she worked in real estate in Sieverodonetsk, a medium-sized city in eastern Ukraine’s Luhansk region. Soon after Russia invaded on February 24, Holovko fled her hometown with her mother, daughter, and dog. In April, she found work with R2P — providing her not only with a job but also with a sense of purpose.

“I forget about my problems when I’m helping other people,” she said. “I am reminded that others are in a far worse situation.”

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine sparked one of the largest geopolitical crises in years, an era-defining event whose consequences have reverberated across the globe. While officials in world capitals debated the war’s implications, many of Ukraine’s 43 million citizens found their lives irreparably upended. More than eight million Ukrainians have fled to other countries. Just under six million more, Holovko included, are internally displaced. International organizations, like HIAS, have mobilized to an unprecedented degree to help Ukrainians and others affected by the war cope with their country’s turmoil. In 2022 alone, HIAS assisted more than 650,000 people affected by the conflict and raised almost $2.7 million in funds to be disbursed directly to those in need.

And yet the story of Ukraine in 2022 is one of a population that has found relief from the war’s trauma in helping each other.

“Usually, you’d have Polish people helping Ukrainians, or Colombian people helping Venezuelans, for example,” said Enrique Torrella, HIAS’ regional director for Africa & Eurasia. “But here you have Ukrainians helping Ukrainians.”

"Usually, you’d have Polish people helping Ukrainians, or Colombian people helping Venezuelans, for example. But here you have Ukrainians helping Ukrainians."Enrique Torrella, HIAS' regional director for Africa & Eurasia

It’s a situation few could have imagined being in a year ago. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is a continuation of hostilities that began nearly eight years before, in 2014. In late 2021, amid reports of Russian troops massing along the Ukrainian border, HIAS began to plan for the possibility of a wider war. Nevertheless, up until February 24, there was widespread skepticism that it would actually happen.

“Every morning around then, I’d get up super early to talk to various NGOs and the UN,” recalled Carrie Taneyhill, HIAS’ director of emergency response. “I remember one conversation where someone said, ‘We’re making all these plans, and they’ll probably just sit on a shelf.’ Eleven hours later, the war started.”

The war began on a Thursday. By Monday, HIAS had already initiated its response, with humanitarian assistance in Poland. Two weeks later, the organization was in Lviv and, before long, had re-established a country office in Ukraine, staffed by experienced professionals from around the world, to bolster capacity even further. As the war’s second year commences, HIAS Ukraine now has three regional offices in addition to its headquarters in Kyiv.

The relaunch of HIAS Ukraine is only the tip of the iceberg. HIAS’ effort, undertaken in the midst of a war, has been staggering. In addition to working with Ukrainians displaced internally, HIAS opened offices in Poland, Moldova, and Romania in order to better serve those who fled to neighboring countries. HIAS also expanded the innovative Welcome Circles private sponsorship program, initially established to resettle Afghans fleeing their country’s takeover by the Taliban, to place Ukrainians with groups of citizens across Europe and the United States. R2P has experienced a similarly meteoric rise: In 2022, it grew from 140 members of staff to over 1,200 and has seen its budget expand seventy-fold.

It’s an expansion fueled by HIAS’ reliance on local organizations and local staff who, like Holovko, are best positioned to relate to the problems faced by those they encounter.

“I’m very proud to be a part of this organization because of its support for internally displaced people,” she said. “We all understand each other’s problems. We’re strong enough to help each other.”

“We all understand each other’s problems. We’re strong enough to help each other.”Anastasia Holovko, regional monitor, Chernivtsi, R2P

As the war in Ukraine enters a second year, there is little indication that hostilities will cease anytime soon. Renewed fighting in the spring is expected, which could worsen the humanitarian crisis.

HIAS expects to be working in the region for some time to come. The organization seeks to highlight the particular challenges faced by vulnerable elements of Ukraine’s population: those with disabilities, women and girls at risk of gender-based violence, members of the Roma community, and non-Ukrainians facing discrimination as they uproot themselves again.

“Additional funding is necessary,” said Erika Alfageme, country director of HIAS Ukraine. “And we’d like to continue building strong partnerships with local organizations. Despite all the difficulties and challenges, I’m proud that we were able to restart our operations here.”

For Holovko, there is little choice but to carry on. Her hometown, Sieverodonetsk, remains under Russian occupation, unreachable except via an occasional phone call to a loved one left behind.

Even if the war ends, she is unsure if she will ever return. “I’m not ready to see what they’ve done to my town,” she said. “I’m not sure I can continue my life there, anyway. I have to build a new life.”

One year into the war, planning for the future remains an impossibility for Ukrainians, where essential survival can be a daily struggle. Even a confessed optimist like Holovko — who cited the famous psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl as a source of inspiration — struggles to rise above the blackouts and shortages that typify war-time Ukraine. But, she says, she simply has to live in each moment. And to keep listening.

“We’re still alive. That’s what’s important.”