Robert Aronson is a member and immediate past chair of the HIAS Board.

In the fall of 1940, as the Nazis were constructing the Warsaw Ghetto and imposing new measures against the Jews, Emmanuel Ringelbloom, a Jewish historian and resident, organized a clandestine group to chronicle life in the ghetto and create a written record of Nazi atrocities. The group, code named Oneg Shabbat (Joy of the Sabbath), was an ambitious effort as well as an illegal one — punishable by death. It strived to preserve the experiences of Jews from all walks of life and reflect the diversity, richness, despair, hopes, daily life, and vitality of the Warsaw Jewish community.

The community faced tremendous challenges. The ghetto was extraordinarily crowded, ultimately packing around 450,000 Jews, 30% of Warsaw’s entire population, into a land mass occupying 2.8% of the city — an average of six to seven people per room. Ghetto residents suffered from starvation diets, economic disruption, rampant poverty, fetid air, typhus, dysentery, corpses strewn on the streets, disease, and random shootings by Nazi guards on top of the imminent threat of deportation to concentration camps. But the archives also depicted the cultural and intellectual resilience of the residents as evidenced by the creation of underground libraries, Jewish schools, youth movements, theaters, synagogues, discussion circles, poetry readings, art exhibitions, and a symphony orchestra. In total, the Oneg Shabbat movement generated over 30,000 pages of material that were surreptitiously buried in metal milk containers that would be unearthed only in the post-war years.

On the hot evening of August 3, 1942, as the Nazis were systematically arresting and deporting what would ultimately amount to 300,000 Jews, a 19-year-old resident named David Graber slipped a signed piece of paper into one of the milk containers at 68 Nowolipki Street with a simple, declarative statement: “What we’ve been unable to shout out to the world, we buried in the ground.” Within two weeks of that statement, Graber was deported to the crematoria of Treblinka.

The archives of the Oneg Shabbat endeavor represent a cry of despair over the tragedy faced by the Jews and the world’s indifference to an unfolding saga of hate and persecution. But it also represents an optimistic and courageous initiative asserting the value and agency of the ghetto’s residents in the face of impending death. It offered a belief that the world would in the future, upon learning of the desecrations described in the archive, prevent the recurrence of the hardships experienced by people subjected to persecution and displacement.

The Oneg Shabbat offers a fascinating glimpse into the past. But it is no mere historical artifact. Eight decades later, the war in Ukraine has again resulted in the mass flight of refugees who seek to forge ahead with their lives amid uncertainty and displacement.

The Oneg Shabbat offers a fascinating glimpse into the past. But it is no mere historical artifact.

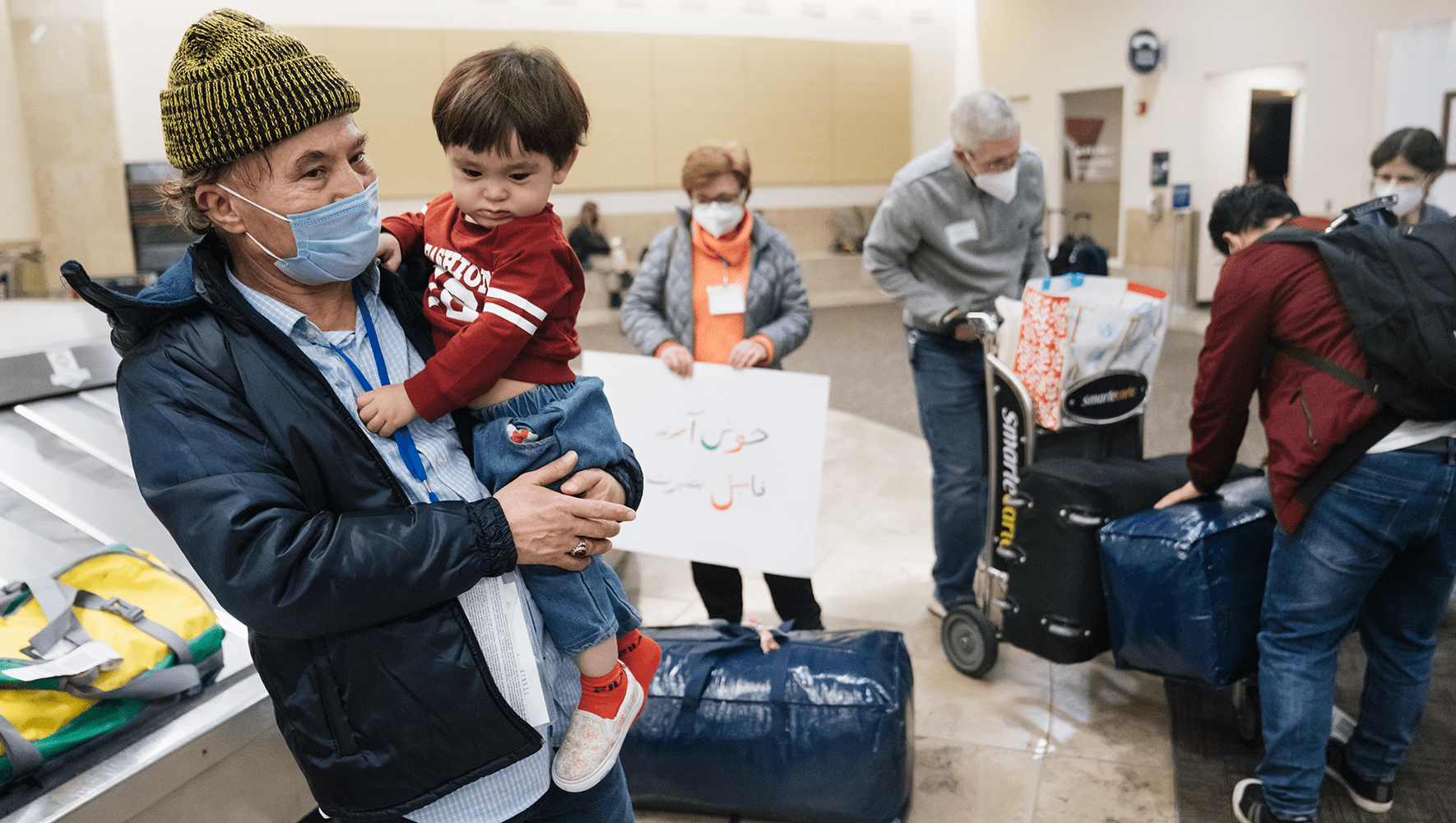

Last month, the HIAS Board traveled to Poland and Moldova to review our programs of protection for refugees mainly from Ukraine, as well as to support the local Jewish communities in their resettlement efforts. Since the start of the Ukraine War in February 2022, some 8 million refugees have sought temporary refuge in Poland, of which 1.5 million are remaining in the country on a long-term basis. Moldova, Europe’s poorest country, has admitted 700,000 more, with around 104,000 seeking long-term protection. The needs of these refugees are immense. In addition to their sheer number — which strains the resources of their host countries — displaced individuals must contend with the risk of gender-based violence, poverty and unemployment, and the psychological toll incurred from abandoning their homes due to a violent conflict.

During the week of our mission, we met with innumerable local resettlement partners, engaged in discussions with Jewish communal and religious leaders, and most importantly, met extensively with refugees from Ukraine. The scope of HIAS’ services to refugees is broad and relevant, examples of which include: protection, empowerment, rights representation, and economic inclusion for women; children’s programs; legal aid to LGBTQ refugees; protection to Roma refugees; medical and housing assistance; mental health and psychosocial support for refugees suffering from trauma; and out-migration services to Western Europe and the United States.

In addition, while our mission was immersive and focused on our work with refugees, we also held meetings with the countries’ Jewish secular and religious leadership. Before World War II, Poland had the world’s second largest Jewish population of 3.3 million — roughly 90% of which was exterminated in the Holocaust and a significant number of survivors subsequently emigrated to Israel or the United States. Today, there are around 14,000 Jews living in Poland. Of the estimated 350,000 Jews living in Moldova in the pre-war period, roughly 90% were killed in the death camps and today’s Jewish population numbers around 15,000.

Nevertheless, there has been a rebirth of Jewish life and vitality in both countries, marked by the creation of Jewish religious, cultural, and communal institutions and a dedicated engagement in the Ukrainian refugee crisis. These communities remember all too well the horrors of the Holocaust and the need to welcome the refugee and protect the stranger as a fundamental precept in Jewish ethics. Their dedication to helping refugees serves as an inspiring invitation to partner with HIAS to uphold our mission of serving refugees regardless of religion, ethnicity, race, or background.

The twin streams of the HIAS commitment to protect refugees and our partnership with the local Jewish communities came together as we, the HIAS Board, served as a representative of American Jewry in the commemoration ceremonies marking the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the 120th anniversary of the Kishinev Pogrom. Whereas the latter incident reminded the global Jewish population that virulent antisemitism would not disappear in the 20th century, the Holocaust bears sobering witness to the application of science and technology to the systematic, industrialized extermination of Jews — starting in the Warsaw Ghetto.

And so it came about that under gray skies and blustery conditions in the former Ghetto area of Warsaw and, several days later, the Jewish neighborhood of Kishinev, we paid tribute to those who suffered and died solely because they were Jewish. In so doing, we honored the legacy of David Graber and Oneg Shabbat in shouting out to the world about the evil of indifference.

While the commemorative ceremonies were deeply moving, the most meaningful moment occurred on the second floor of a dormitory created by HIAS in Chisinau, Moldova for autistic refugee children and their families. There I met Nina, the Ukrainian grandmother of an autistic child. When she asked me what I was doing at the facility, I answered that I was on the board of an American Jewish agency that came to Moldova to assist Ukrainian refugees, by providing programs such as the one in which her grandchild was enrolled. Nina was silent for a moment and then burst into tears of joy and gratitude.

She knew at that moment, amid the cruelty of a war and the disorientation of her refugee journey, she was not alone.