Designing a Crash Course for New Americans

By Sara Gelb, Refugee Resettlement Intern

Nov 24, 2015

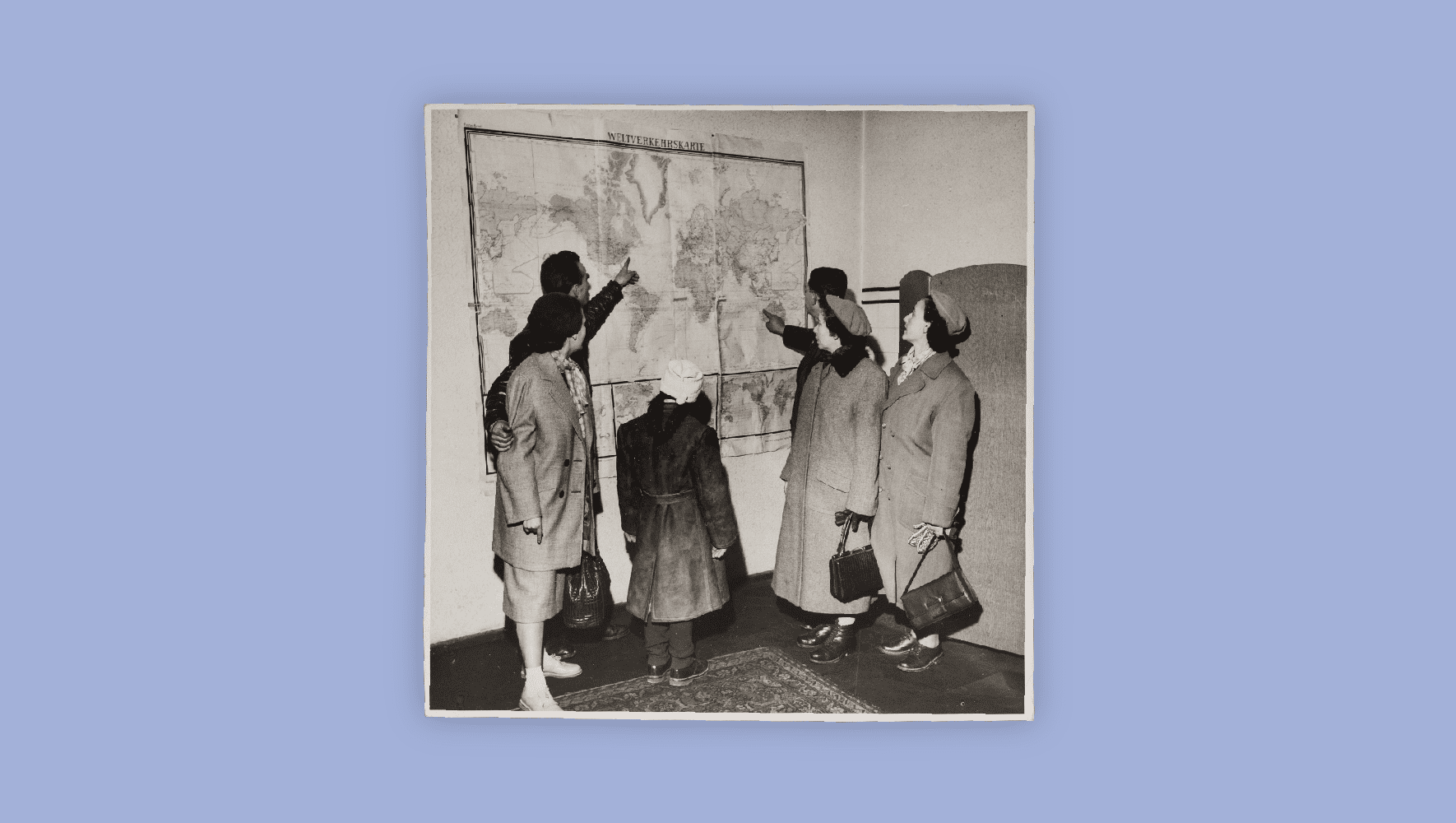

Sara Gelb, HIAS Refugee Resettlement Intern

(Photo courtesy of author)

Imagine greeting a family at the airport who have just escaped persecution in their native land. You are the first person they interact with in this country. What would you need to teach them right away in order to facilitate a smooth adjustment process? Would your answers change depending on where the refugees are from?

Cultural orientation, teaching refugees about their new country and its customs, is an important part of the resettlement process and is required by the State Department. It covers fifteen topics, ranging from U.S. government and laws to budget and finance.

The refugees welcomed to the United States each year by HIAS and other resettlement organizations are a diverse group and have different needs when it comes to orientation. Some may come from remote villages and have had limited opportunities for formal education. Others, however, may have entirely different backgrounds. Think, for example, of an Iranian family coming to America to escape an oppressive regime. Maybe they lived in the highly urban and modern Tehran, and perhaps both parents were university professors who are fluent in English. Their children have gone to school since they were five and know a little English. This family clearly understands the importance of education, and they definitely know basic hygiene and dental care. So what sort of orientation would they need?

Since this family is leaving a country with a religious government and strict laws based on conservative religious beliefs, they will likely need to learn about the American legal system. They may be surprised at the level of freedom in the United States. The family will have to learn about our education and health care systems, which are distinctly different from those in Iran. Perhaps most importantly, they may have to learn that their skills and former experience are not easily transferrable in America. It may be extremely hard for the parents to find jobs at the caliber they are used to, and this can damage self-esteem.

During my internship, as I created orientation materials for highly educated individuals from modern countries, I often thought of a family like this one, and what their specific needs might be. I also thought about my own family’s experience as refugees. My grandmother, Judith, is a Holocaust survivor. She evaded the Nazis for three years by moving from her home in Slovakia to the home of Hungarian relatives, and then to Hungarian forests. She was ultimately captured and taken to a concentration camp in Germany, where she remained until it was liberated. After the war, she moved to England and then Israel before settling in America.

How hard it must have been for her to navigate these new surroundings on her own, especially after all the trauma she endured. Some sort of orientation would have made a huge difference in easing her transitions and it was meaningful for me to be able to work on such services. I hope that the materials I worked on will allow refugees to more easily adjust to their new lives, so they can overcome their pasts of violence, injustice, and persecution.