The Cinderblock Welcome

By Allison Mandeville, HIAS Intern

Jul 31, 2013

After passing through a metal detector and barbed wire fence, visitors to Delaney Hall Detention Facility are greeted by a white cinderblock wall splashed with the word “Welcome!” in Spanish, Russian, Arabic, and French. The detector, the fence, and the wall mark the start of each trip that HIAS’ “Know Your Rights” team makes to the Newark, New Jersey detention center. It is an ironic, and yet somehow fitting, set-up. While I would hardly describe the facility as “welcoming,” it is here that hundreds of immigrants form their first impression of the United States.

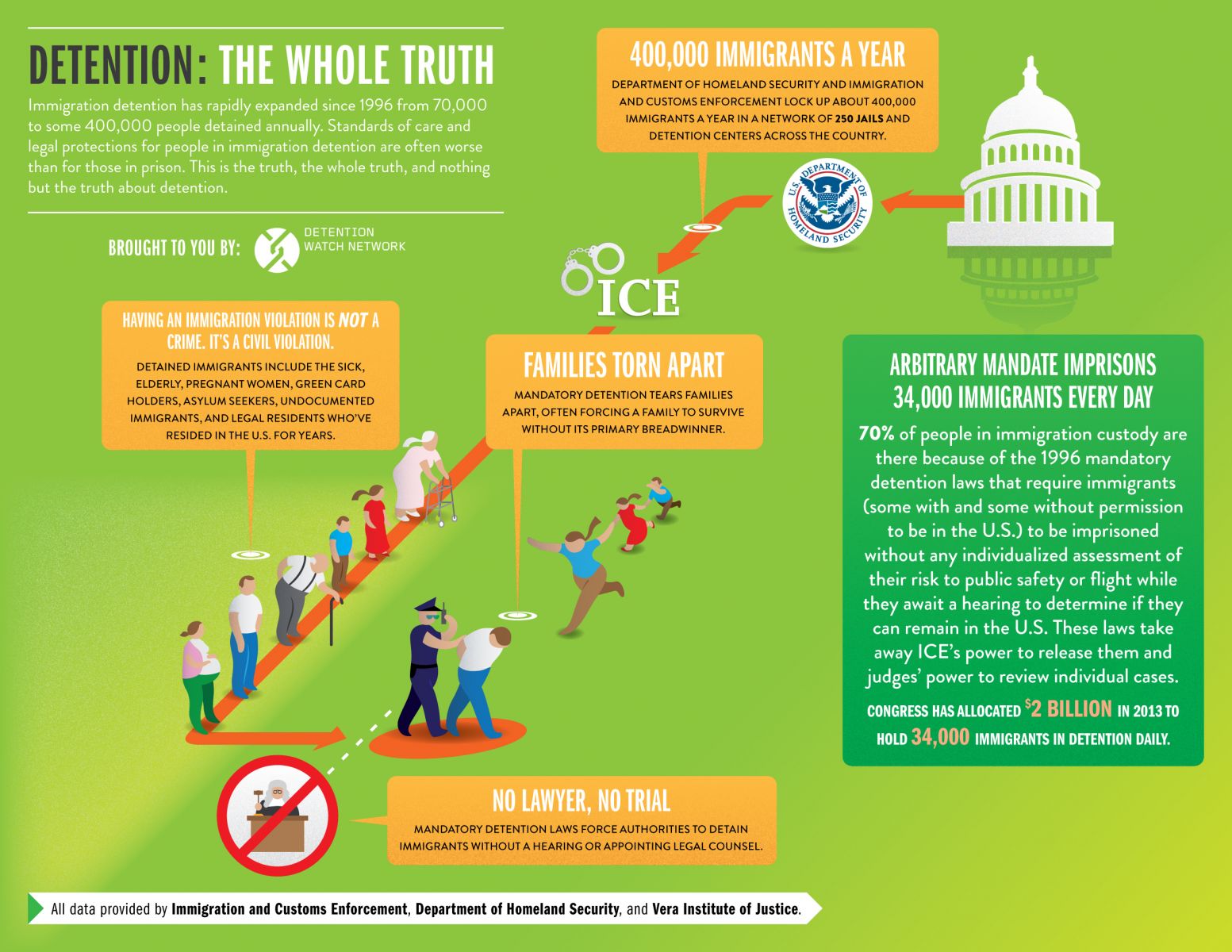

As a summer intern with HIAS in New York and a fluent Spanish speaker, I have spent two days each week at Delaney Hall, serving as an interpreter for the incredible team that conducts intake interviews, provides legal counsel, and works to locate pro bono attorneys and social service providers for the dozens of asylum seekers and other immigrants detained there. The path to Delaney varies greatly from case to case, but common stories include unsuccessful border crossings, ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) raids on homes or places of employment, and arrests at the airport upon attempted entry (e.g. no or invalid documents, or immediate requests for asylum). Operating within the Detained Torture Survivors’ Legal Support Network, HIAS has screened over 400 detainees since November 2012 and conducted “Know Your Rights” presentations for over 90 attendees at a time.

Logistically speaking, the huge number of incoming detainees and the extreme complexity of the immigration system mean that our legal team is in constant demand at Delaney Hall. We may conduct up to 16 new interviews per day, while also responding to follow-up questions from individuals grappling with legal jargon, court hearings, and lengthy asylum applications in a language they do not know. On some days, lines of people waiting to consult with us snake through the hallways surrounding the room that serves as our office. Ever respectful and patient, they arrange neat rows of chairs as they wait and compile lists of names to ensure that no one misses their turn.

The orderliness of the waiting area provides a tiny glimpse into the nature of the individuals I have met this summer. Despite being shrouded behind cinderblock walls, isolated from family and friends, and clothed in identical dark red cotton uniforms, the occupants of Delaney Hall are an inspiration to me in that they have maintained and are able to convey to us, a group of total strangers, their individual hopes and dignity.

For many at Delaney Hall, their meeting with the HIAS team is the first opportunity they have had since being detained to sit down with another human being and share what is most often a tale of both extreme suffering and extreme perseverance. In hearing their stories and in observing the strength with which they carry themselves on a daily basis, I have learned as much from these men and women about basic, infallible aspects of human optimism as I have from my HIAS mentors about immigration and asylum law.

I have also learned that the role of “interpreter” is not nearly as simple as it sounds. In order to convey a story of Central American gang violence or an escape from paramilitary ferocity, I must first have this brutality explained to me by its victim, often in excruciating detail. Once I have clearly relayed this information to my colleagues, I must transmit back their similarly detailed explanation of corresponding legal options. In this sense, I have become the ultimate student this summer - absorbing facts, histories, and fears on the spot so as to bring everyone at the table to a mutual understanding. Through this communication and ongoing interaction, we are able to take stock of what has happened in the past and make plans for what must happen moving forward.

Each time our team reaches this intersection of understanding and action, I am reminded of the importance of the work that HIAS does, bridging the gap between the human suffering that leads to migration and the legal structures that seek to provide sustainable relief to such suffering. Throughout my various stages of legal, emotional, and linguistic education this summer, I have been struck constantly by how challenging and yet truly life-changing this effort can be. It is with this in mind that our team chooses to confront the challenges, gather the stories, and explore the solutions, passing through the detector and the barbed wire again and again to arrive at the cinderblock “Welcome!”