Many of the hundreds of HIAS staff around the world were once refugees themselves. In our new series Refugees Supporting Refugees, we tell these colleagues’ stories. Read earlier articles in this series here.

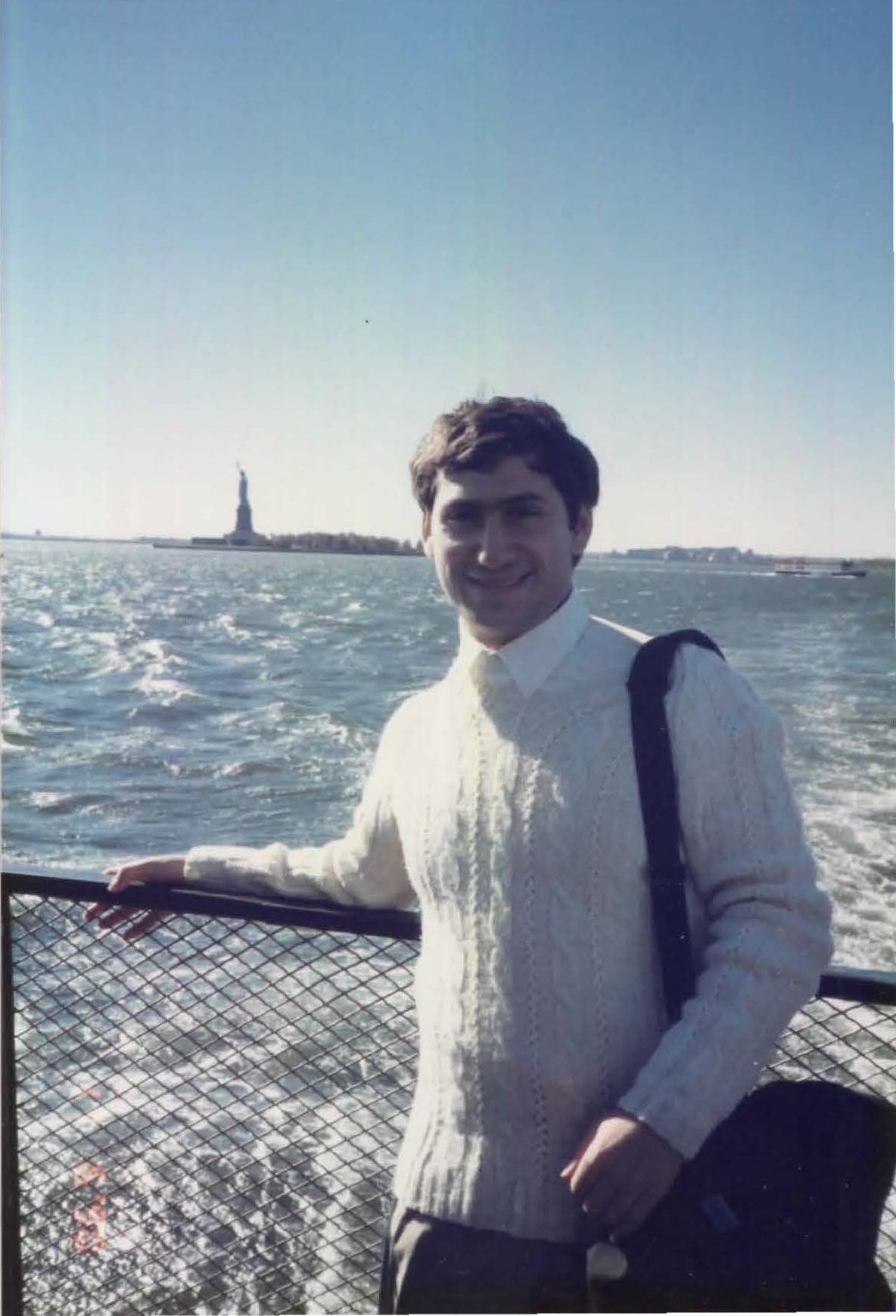

This November, Igor Chubaryov will hit a major career milestone — 35 years of working at HIAS. As HIAS’ longest-tenured current employee, Chubaryov has held various roles over the years, from greeting clients at the airport to fielding immigration questions by phone. But his history with HIAS actually began before he worked there at all, when he landed at an airport in Vienna in 1989 as a stateless refugee after fleeing the Soviet Union.

As a child growing up in central Russia, Chubaryov’s life seemed largely normal until he reached his early teens. Then he began to experience a constant barrage of antisemitism. His school peers bullied him, beat him up, and called him slurs like “Judas.” Changing schools didn’t help — each time, his classmates would identify him as Jewish based on information on the classroom roster, and the mistreatment would begin anew.

“It was useless to even say anything to teachers — then you’d get beaten up for complaining,” said Chubaryov, who was often singled out by his instructors for extra cleaning work. “I learned early on to keep my mouth shut. I just tried to avoid it — I missed a lot of school because of that.”

As he grew older, Chubaryov became increasingly disillusioned with Soviet life and politics. His college professors warned that he needed to keep his opinions to himself. Instead, he made friends with refuseniks — Jewish people denied exit visas by the U.S.S.R. — who helped him explore his growing interest in Jewish history and culture, including Hebrew and Yiddish literature. As policies against emigration loosened under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, Chubaryov’s friends began leaving the U.S.S.R.

“As soon as my friends started getting permission to leave, I told my parents, ‘We have a window of opportunity for me. I’m going to use it,’” he recalled. “My father was worried that they might do something to me. But [one day] they called me and said you’re free to leave.”

Freedom came with a price — relinquishing his citizenship and becoming stateless. Still, in January 1989, a 24-year-old Chubaryov took a flight to Vienna, with no legal status or concrete plan for where he would go next. A HIAS employee met those coming off the plane and offered them assistance. Over the following months, first in Vienna and then in Rome, HIAS helped Chubaryov navigate the process to be recognized as a refugee and resettle in the U.S.

“HIAS helped me file the application, and to obtain an interview with the immigration official. If not for HIAS, it would have been extremely difficult for me. I don’t know if I would have been able to successfully obtain refugee status. How would I know where to go, who to present my case to?”

If not for HIAS, I don't know if I would have been able to successfully obtain refugee status. How would I know where to go, who to present my case to?Igor Chubaryov

After a few months in the U.S., Chubaryov started working for HIAS — and the roles reversed. Now, he was the one meeting other newly arrived refugees at the airport and helping them navigate their way to their next destination. Even still, he imagined that he’d only work for HIAS temporarily — perhaps six months or a year — before figuring out what he wanted to do. Thirty-five years later, he’s still here.

“HIAS draws people who want to help others, and with those coworkers and the mission, I felt HIAS was my home and just continued working,” he said. “You know, one year, three years, 10 years … my job changed throughout the years, but I didn’t think about leaving.”

Today, Chubaryov works as a Department of Justice (DOJ) Accredited Representative with HIAS’ U.S. legal and asylum department — a certification which allows him as a non-lawyer to represent clients in matters involving U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). In this role, he supports HIAS’ U.S. legal team as they help HIAS clients navigate a complex immigration system.

A lover of languages — Chubaryov speaks Russian, English, French, Spanish, Hebrew, and a little Yiddish — he frequently helps his colleagues with translation. These skills have allowed HIAS to help fill a gap in services for Francophone asylum seekers arriving in New York from countries like Guinea and Cote d’Ivoire.

HIAS draws people who want to help others, and with those coworkers and the mission, I felt HIAS was my home ... My job changed throughout the years, but I didn’t think about leaving.Igor Chubaryov

As the third generation in his family to have been displaced by antisemitic violence and attitudes, Chubaryov sees himself as having broken the cycle by coming to the U.S. His father’s parents had to flee their shtetl (small Jewish town) in Ukraine due to a pogrom — an organized massacre of Jewish people. During World War II, his grandparents and parents, then four and five years old, had to flee Ukraine deep into the Russian territory to avoid Nazi occupation.

“I hope I’m the last in my family to experience this. Psychologically, financially, culturally, it’s very taxing. It’s like [coming to] a different world.”

This long history of displacement connects Chubaryov to his work at HIAS, where he sees empathy as an essential trait.

“You’re still thinking about back home, your parents, your country, your friends — one foot here, and one foot there. It takes time to settle down, to overcome the difficulties. Sometimes people feel better if you tell them, listen, I went through this myself.”

You’re still thinking about back home, your parents, your country, your friends — one foot here, and one foot there. It takes time to settle down, to overcome the difficulties. Sometimes people feel better if you tell them, listen, I went through this myself.Igor Chubaryov

The deep connections he forms with clients often pay off many years after his initial contact with them, when he hears that they’ve hit another major milestone.

“I am very happy when, five or six years later, I get a text [saying], ‘Igor, we just got sworn in and became U.S. citizens,’ and then there’s a picture of the family,” said Chubaryov. “One thing I can say about my job, it’s very rewarding.”