Mia Farrow Honors Humanitarian Workers Between Desert and War

By Dan Friedman, HIAS.org

Aug 19, 2021

Mia Farrow (R) and humanitarian worker Gaele Chojnowicz in Chad, 2009.

(Courtesy Mia Farrow)

Just over a decade ago, actor and humanitarian Mia Farrow went to Eastern Chad to visit the survivors of the genocide in Western Sudan. Inspired by an earlier visit to Darfur she had made with her son, Ronan, she went to the Goz Amir camp to document the cultural traditions of the refugees from Darfur, cultures and traditions that were in danger of dying out, torn from the villages and lands that gave them life.

Farrow made 14 trips to Chad before the pandemic, but on this trip in 2009 she stayed at the HIAS compound for a month after she was welcomed by a HIAS worker on her arrival. “A most wonderful young woman, Gaele Chojnowicz met me when I arrived at the gate and let me stay. On Fridays, we had Shabbat!”

To mark World Humanitarian Day on August 19, HIAS spoke with Farrow about her deep admiration for the aid workers and the work they do. “I feel humble to have been among them. Humbled by the realization of how little most of us do for others, [yet] these people do everything, every day, in perilous and deprived conditions -- in war zones. They are there.”

“While I was there, we notified EUFOR [the European Union peacekeeping force] because it was so remote. During the entire month that I was on that Chad-Darfur border, they were under attack from a militia known as Janjaweed. Bands on camels came to loot and burn refugee camps, Chad villages and anyone else who was there. At night, I kept my backpack ready to flee.”

She lived and worked among humanitarian aid workers who went daily into the camps to provide food and support for the survivors of the genocide carried out by President Omar Al-Bashir, the Janjaweed, and other allies. While she was there, the villages were newly-displaced, in mourning for those slaughtered in Darfur.

Today, the situation is different, but not much better. Although former President al-Bashir — charged by the International Criminal Court for genocide — is in Sudanese custody, the villagers are still mostly in camps in Eastern Chad. Militia attacks have lessened, but the pandemic has isolated them from the surrounding community, climate change is worsening the already arid conditions, and, due to continued political instability in Darfur, Sudanese are still fleeing to Chad.

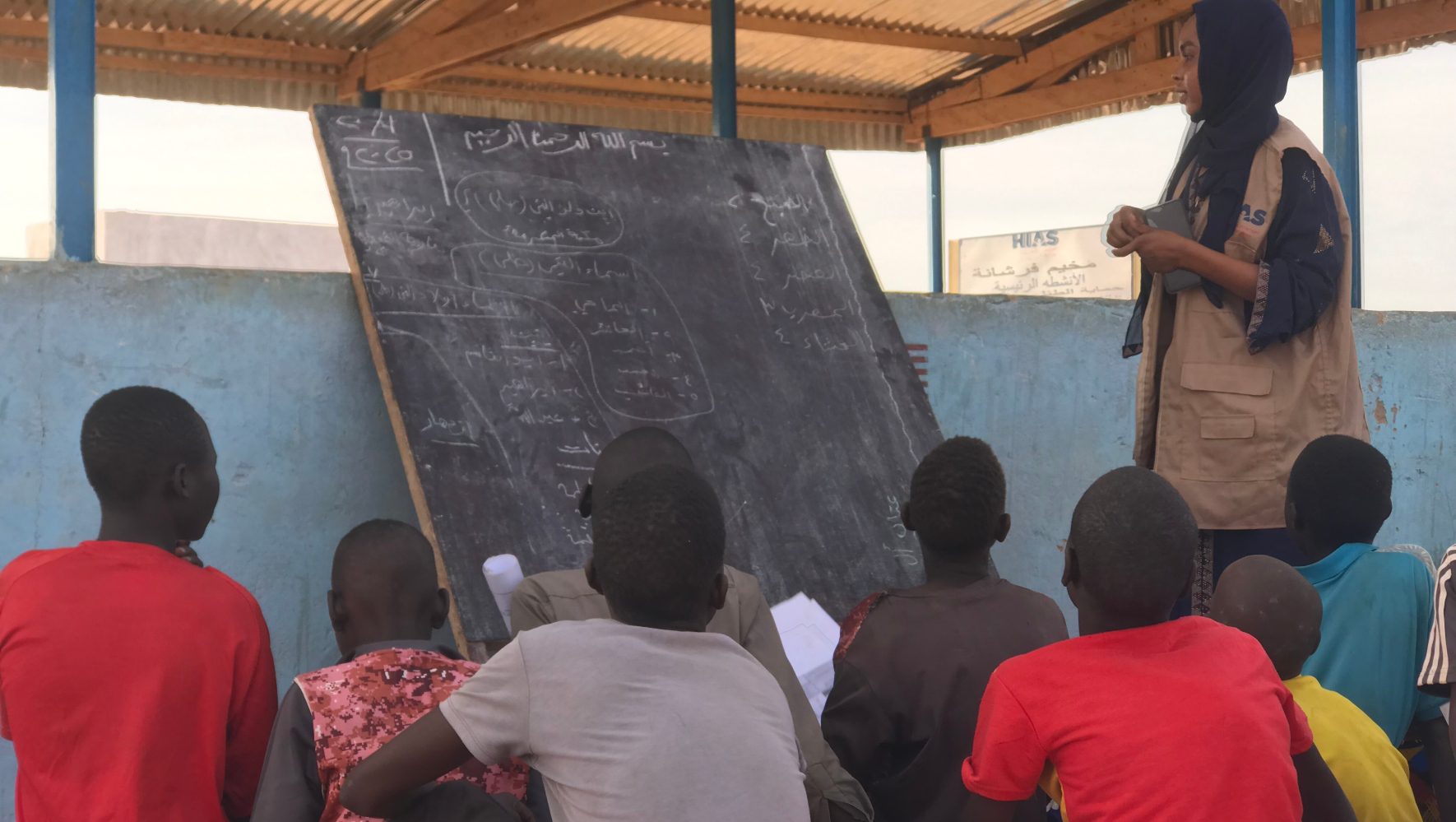

HIAS Chad was founded in 2005 in response to the first wave of refugees from Darfur. Country Director Roch Souabedet now supervises over 100 staff who work in 13 refugee camps and a single “site” — Kerfi is known as a “site” because it is too temporary to even be called a camp.

In each of these locations, HIAS works with UNHCR to distribute food, but its role is more than just providing basic physical sustenance. “Every day, the field workers walk through the camps to help build mental health and to provide psycho-social support,” said Souabedet. “This has many components — first of all, psychological first aid, post-traumatic treatment to create resilience.”

If the Sudanese are clinically sick, then the fieldworkers refer them to qualified medical personnel, but on a day-to-day basis, HIAS workers help these forcibly dislocated villagers to move past the traumatic loss to create a sense of community and safety in the camps. That’s not always so easy because although there are over 500,000 refugees in Chad, they are deeply fragmented. Even the 14 HIAS locations represent six separate ethnicities, each of which includes a number of culturally distinct villages.

Rachel Levitan, HIAS’ Vice President of International Programs embraces that diversity. "As a Jewish humanitarian organization, HIAS seeks to recognize and uphold the rights of people displaced because of persecution. Working closely with Darfuri communities in Eastern Chad — including imams, women leaders, and community elders — we do all we can to listen to, respect, and respond to community needs and enable durable solutions."

One of the initiatives that Souabedet is most proud of is the improved bread-making activities in which inhabitants at all of the HIAS camps participated. It’s a universal skill that can build personal and communal resilience. Staff work with survivors of gender-based violence to build ovens and make breads which can help them build both self-reliance and also self-worth.

Many of the people in the camp have suffered such violence which makes them doubly-isolated because in many cultures, survivors of abuse are stigmatized. In trying to provide therapy, HIAS workers are faced with obstacles. For example, early marriages are accepted as norms by some of the cultures in the camps, meaning that girls as young as 12 can be in a forced marriage.

But HIAS workers engage with these survivors. Currently wearing protective equipment because of COVID-19, workers join refugee committees and mobilize the community. Among other things, they provide assistance to older people — distributing raw materials for various hand-crafting activities including matting and pottery. These are part of the therapeutic activities initiated by HIAS Chad to help them move on from the past and enjoy life once again.

Another recent project — that helps include all parts of society, including older people — has been the introduction of permagardening which helps engage many who have been pushed from their traditional farms to an arid zone that’s almost a desert.

Farrow remembers one of her visits when villagers nurtured young plants as if they were babies. “They’d shelter them from the wind to make sure they weren’t baked by the sun. They would share their water with them.” If the earth can still bring forth life, these villagers believed, then maybe there was something worth living for.

World Humanitarian Day is a moment to stop and think about the people who are working with clients in some of the hardest places in the world. As Souabedet says, it’s an opportunity to give a “big thank you to our colleagues in the field.”

“I don’t know better people than these aid workers,” says Farrow. “They aren’t celebrated, there are no end-of-year awards for them. They risk their lives and give up everything, to give everything.”