Dispatch: Welcoming Afghans Who Made It to the U.S.

By Andrea Gagne, Public Affairs Officer

Sep 24, 2021

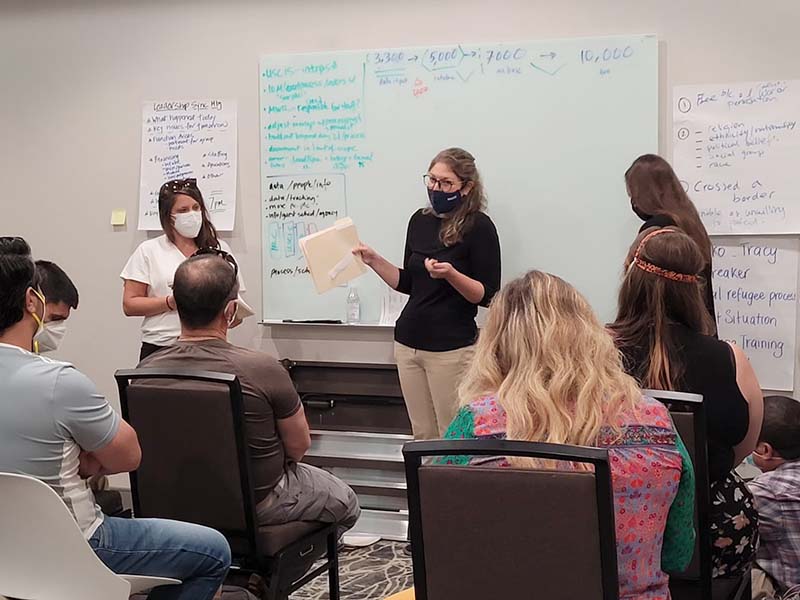

In August and September 2021, in response to an urgent call for assistance, HIAS deployed more than a dozen staff members to military bases across the United States to help with reception and processing of tens of thousands of Afghan citizens airlifted from Kabul in the days before the final withdrawal of U.S. forces. Public Affairs Officer Andrea Gagne worked at Fort Bliss in Texas and Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, conducting intake interviews with relocated Afghans and also training new deployees and conducting quality control.

I recently returned from a three week deployment at two U.S. military bases where I was helping to process some of the thousands of Afghans evacuated by the United States, and I’m not going to sugar coat it: things were difficult.

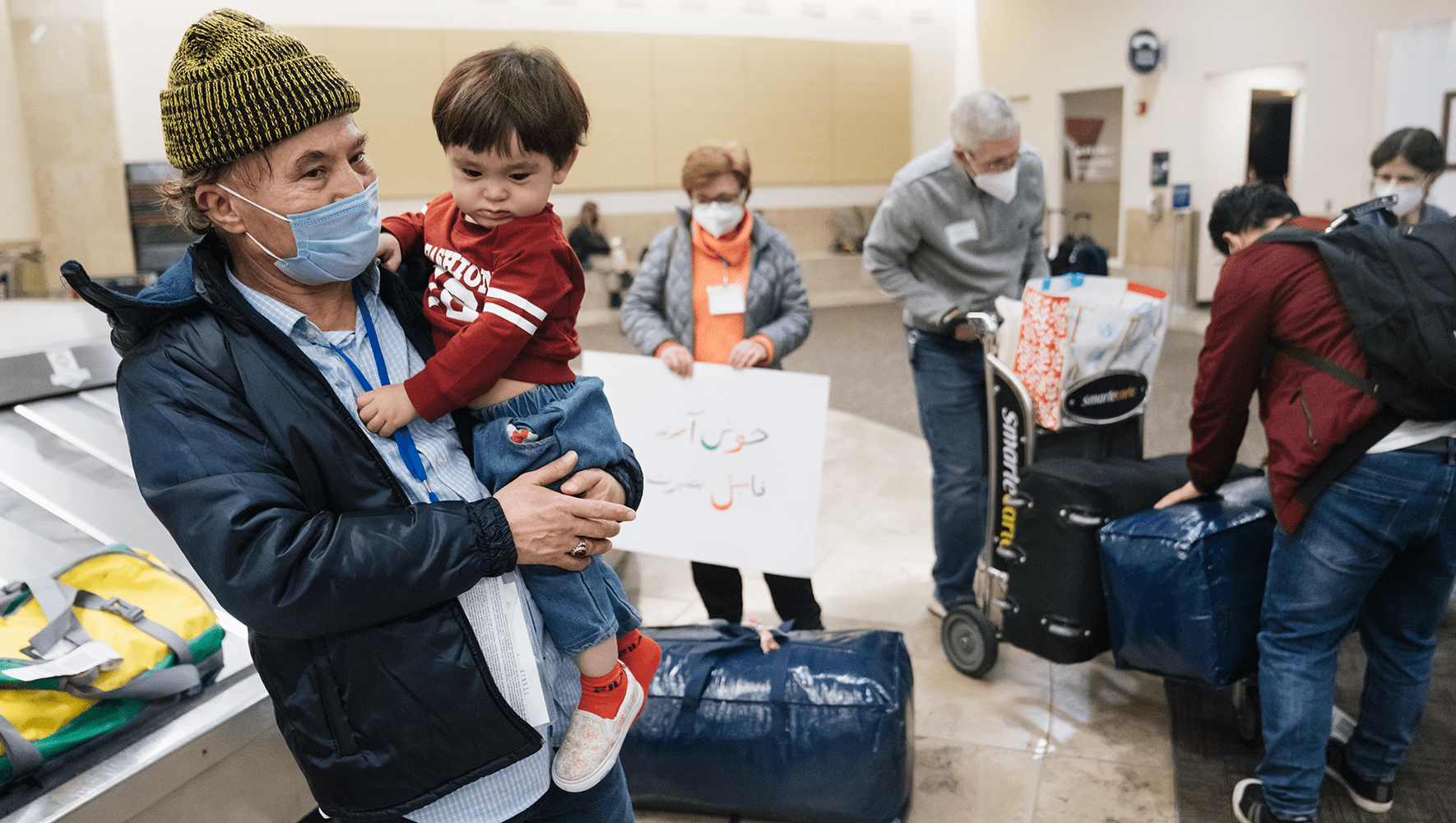

Many of the Afghan citizens I met, whether holders of Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) or those granted humanitarian parole, arrived in the U.S traumatized, swept up in a panic. Some had lost their luggage on the way, others didn’t have time to pack at all. Families were separated, sometimes right on the tarmac in Kabul airport.

Some children arrived with no shoes on their feet, no diapers, with literally nothing. I saw a young girl around 4-years-old who had arrived barefoot having her feet treated because the skin had been torn by the hot, sharp rocks at the base, her first steps on free soil literally burning her soles. After army doctors treated the wounds, they found a new pair of pink sneakers for her. They were at least a couple of sizes too big, but she was thrilled.

Twenty years of American occupation shaped a whole section of Afghan society. Over the course of my time on the bases I met Afghan translators and interpreters, as you might expect, but also doctors, professors, female police officers, shopkeepers, cleaners, aid workers, housewives, pilots, and even an 11-day-old-baby.

Some expressed pure joy to be here. Especially the large number of children, like the little girl who squealed with excitement as she held out her hand while a row of thirty resettlement workers and volunteers walked by, each one of us giving her a fist bump; or the kids who brought us the pictures they drew while waiting for their parents to finish their interviews. We taped their artwork to the walls on the “Coloring Wall of Fame.”

Others cried as they told me about their families and how they were torn from them as they raced to board planes. A little boy around 8-years-old told me about being disoriented, surrounded by tear gas and beaten by a Taliban fighter as he made his way to the airport. Numerous times during my deployment the interpreters we were working with broke down into tears during interviews because a story was too overwhelming to bear.

My fellow HIAS staffers and I, and colleagues from other agencies, did our best to make this situation less difficult. Welcoming and processing so many people on U.S. soil in such a short period of time has never been attempted before and it was not unusual for us to work nine or ten hours on base and then stay up late into the night back at our hotel figuring out operational logistics, filling out forms and paperwork in an effort to get everyone to their new homes and communities as quickly as possible.

The response to the arrivals has been massive, but so is the need. Creating a dignified living environment for thousands of civilians who arrived at the bases suddenly was a huge challenge. When it rained, the ground around the fresh construction sites where new canvas tents for living quarters were erected turned to a muddy sludge. Food was available but varied from site to site, and in some cases people had to wait unshaded in the hot sun for long periods of time to pick up their boxed meals. Still, I did see conditions improve by the end of my deployment.

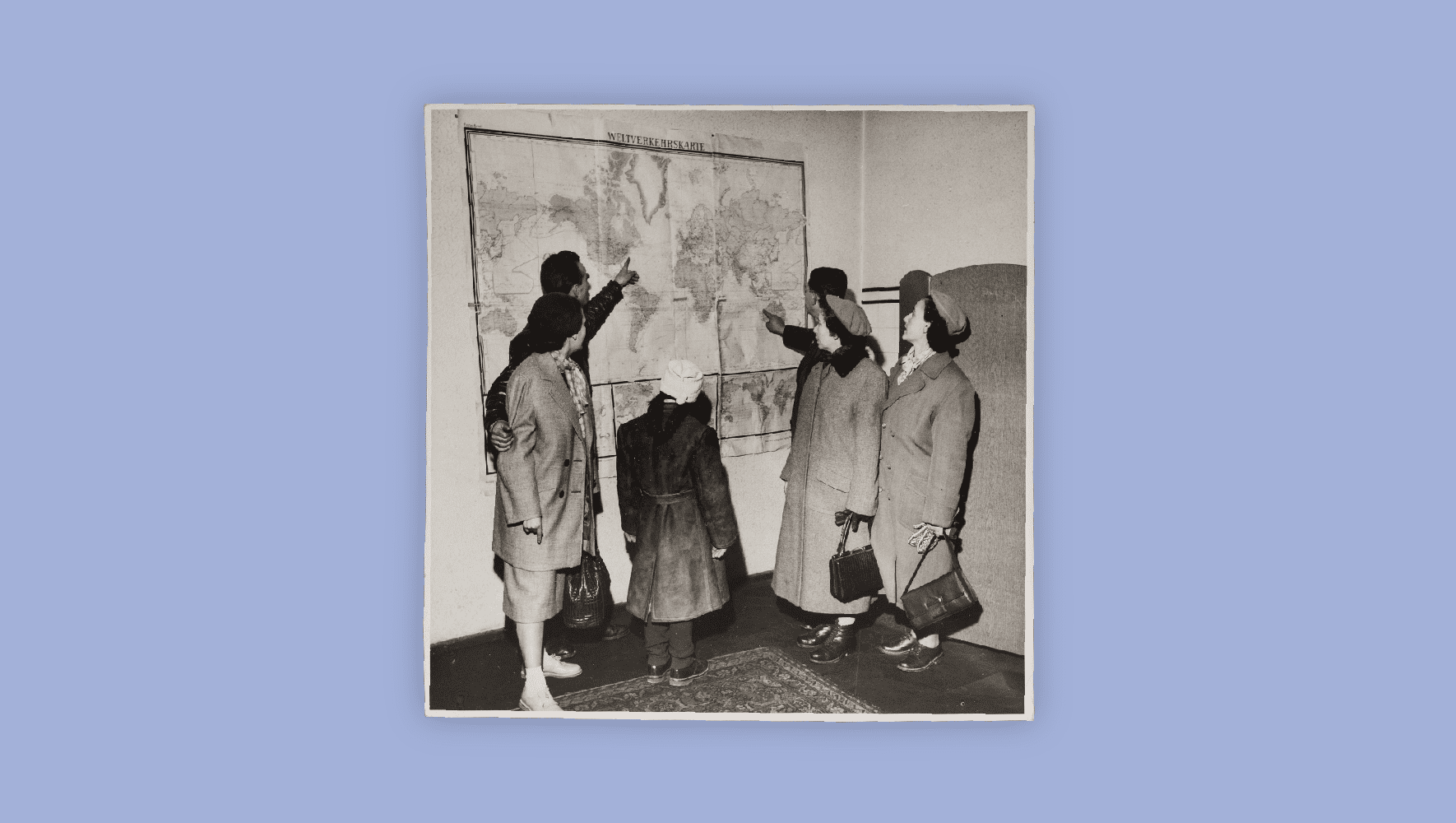

For all the difficulty, I am hopeful, though, as I think of my great grandfather Simon who came through Ellis Island in the 1910s to escape rising antisemitism in Europe. He was one of the lucky few who got out before tragedy struck. At the HIAS desk on Ellis Island he sat across from someone who told him “I know this is hard, but we’re here to help.”

As I sat on the other side of the desk and said the same thing to the families arriving in a strange new place, I thought about how their great grandchildren will be the ones sitting on the other side of the desk a century from now, proud Afghan Americans, ready to welcome the next group of people in need.