Yaasir's Fight for Asylum Comes to an End

By Kerry Honan, Guest Contributor

Jan 04, 2018

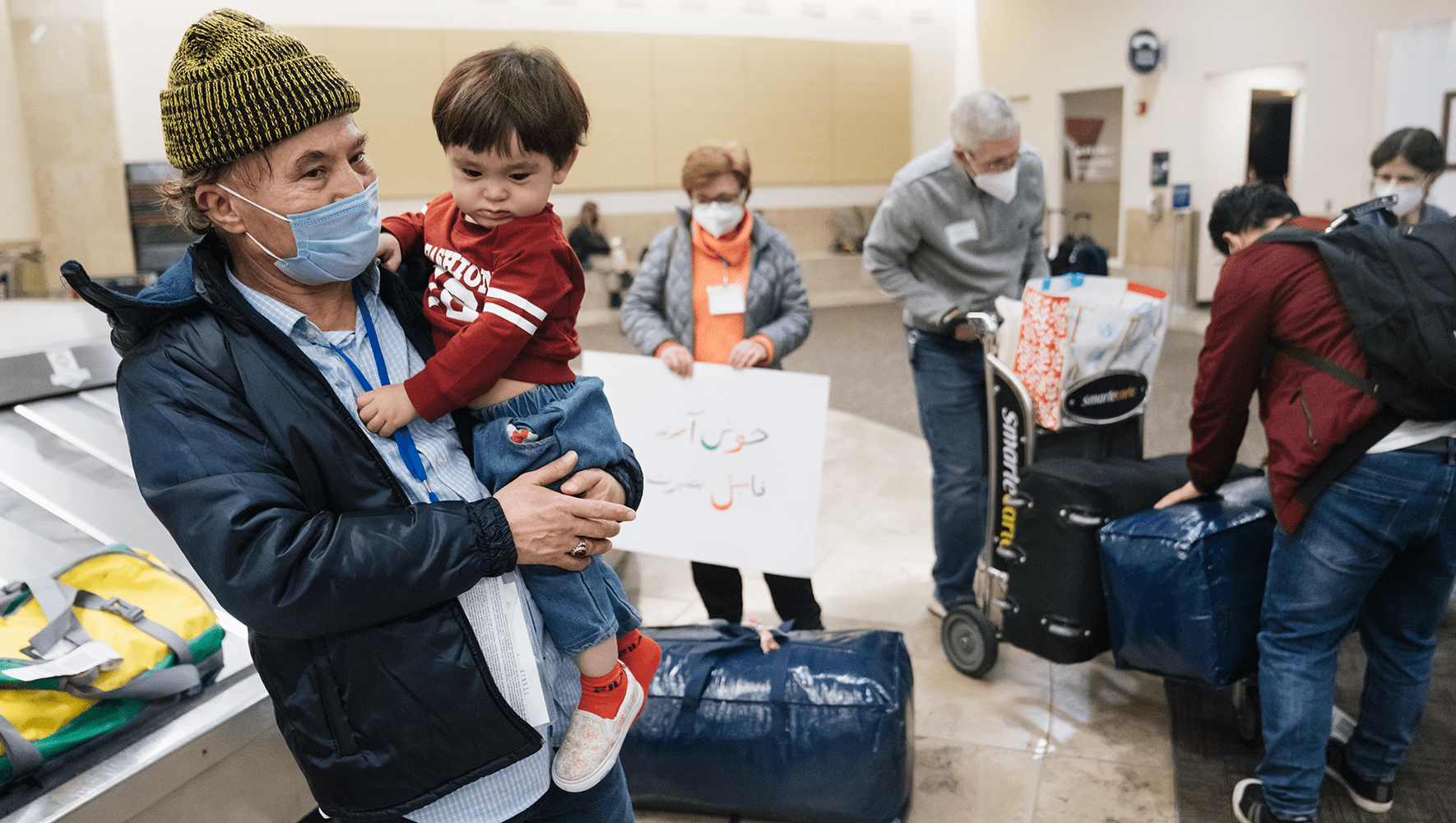

HIAS Managing Attorney Megan Jordi Brody (L) poses with Yaasir (R) outside the courthouse in Baltimore, Maryland after winning his asylum case, September 2017.

(HIAS)

Yaasir* is no stranger to violence, death, and loss. Growing up in Mogadishu amidst Somalia's raging civil war, Yaasir recalls frequent trips to his family's designated safe haven (an area that was a good six hour walk from their home), where they would wait until the grenades and shootings had subsided.

Though these aggressions were rarely directed at Yaasir's family, who belonged to a lower-class, minority clan called Silcis, their lives were often caught in the crossfire of more powerful clans such as Habar Gidir and Abgall.

Tribal, or clan, affiliation is a central characteristic of Somali culture. Though, like many of his generation, Yaasir rejects clan distinction, its role in and impact on his life is undeniable.

"Clan affiliation is not important to me," Yaasir wrote in the detailed declaration that he prepared for his asylum case, "but I knew I was defined by others by my affiliation. Tribal affiliation is a way of life. Members stay together for protection from other tribes and so they can protect their land, since the government is not reliable."

Indeed, according to HIAS Program Associate Ayaan Moussa, who assisted with Somali translations throughout Yaasir's case, Somalis tend to assess and categorize one another by clan in initial encounters. It's easy to know what clan a person is affiliated with, Ayaan said, through simply observing how he speaks, looks, and what his name is.

Yaasir even remembers his grandmother regularly cautioning him from playing with children from more powerful clans. Though seemingly extreme, her apprehensions were not unfounded; by the time Yaasir was a teenager, two of his uncles had been shot by members of Habar Gidir and his older brother had fled to Australia to escape death threats.

Reflecting on his family's approach to life in Somalia, Yaasir wrote, "Death is a regular part of life, and people often act as if any day could be their last." And the family's gravest concerns were often directed at Yaasir and his brothers, who were targeted by other clans and at high risk of forced recruitment by youth-led terrorist groups like al-Shabaab.

When he was around 14, despite his grandmother's warnings, Yaasir was playing soccer with some boys from Habar Gidir and got into a bit of a scuffle. Afterward, Habar Gidir police came to his home and – despite his parents' desperate attempts to stop them – blindfolded Yaasir and took him away. For the two days that Yaasir was held in prison, he was given neither food nor water and beaten harshly. Though his father finally bribed the police with a hefty sum to release his son, Yaasir suffered migraines and temporary vision issues for weeks afterward. Unable to afford x-rays, he treated these serious ailments with only basic painkillers.

Prohibited from interacting with other teenagers, Yaasir became isolated and soon dropped out of school, instead working to support his struggling family. Things were calm for a time, but Yaasir soon fell in love with a girl from a more powerful clan and impregnated her. Upon discovering her condition, the girl's brothers swore to kill him, demonstrating their intent by beating one of his friends so badly that he was hospitalized.

Yaasir's father was furious to hear what he had done but knew that, in order to live, Yaasir would have to leave Somalia. Heeding his father's advice, Yaasir promptly fled to South Africa, where there was already a substantial Somali community. He was forced to leave so quickly that he could not say goodbye to his lover, whom he never saw again.

At first, it seemed to Yaasir that he could create a more stable life for himself in South Africa. Living amongst members of his own clan, he opened a small business selling food and drinks along a shipping seaport and, after a few months, married a Somali woman named Hodan*. It did not take long, however, before Yaasir began to encounter severe discrimination and abuse by hostile South Africans. His store was repeatedly robbed and both he and his wife experienced assault on various occasions.

Moreover, due to his lack of documentation, Yaasir had to constantly run from the police, and neither he nor Hodan, who soon became pregnant, had access to healthcare. Tired of the aggression and fear, Yaasir insisted that Hodan return to Somalia to birth their child with family. Still, his father warned him that he'd likely be killed if he returned.

With Hodan back in Somalia, Yaasir booked a ticket to Brazil, the cheapest destination he could find. From Brazil he made his way, largely on foot, through South and Central America and entered the U.S. via the Mexican border. Upon pleading asylum on U.S. soil, he was immediately detained and held for over a year in an ICE facility.

Unsurprised by the most alarming parts of his story, Ayaan was most shocked by the details of Yaasir's journey as she translated on his behalf. When she herself came to U.S. from Somalia at age ten, Ayaan took a direct flight from Somalia to D.C. and was received by extended family at the airport.

"The fact that people are willing to go through these treacherous journeys and confront countless unknowns in order to maybe make it to the U.S. safely," Ayaan reflected in a recent interview, "indicates that things in Somalia are even worse than they were before." Yaasir's life in Somalia was so horrible, she said, that he felt he had nothing to lose by taking those risks.

Not long after Yaasir was detained, HIAS' D.C. Area legal team took on his asylum case, initially represented by former HIAS Attorney Natasha Kirk. In September, after a long and challenging fight – throughout which he was regularly visited by HIAS' Managing Attorney Megan Jordi Brody – Yaasir was granted asylum and, thus, became officially eligible for protection by the U.S. government.

After being released from detention, Yaasir joyfully went to live with his brother in Denver, Colorado and is now petitioning to bring his wife and daughter to the U.S.

Though overcome with gratitude and relief for his newfound asylum – which he could not have been granted without HIAS' help – Yaasir worries every day for the wellbeing of his family. He instructs Hodan not to leave his family's home but fears that she might be harmed by the violence surrounding her.

"Though I am 22," Yaasir wrote at the end of his declaration, "I have never known a day of peace. I lived through civil war, civil unrest, and clan disputes. Because of the violence and my membership in a low clan, I was not able to get a proper education. I do not want this future for my children."

*Name has been changed to protect the privacy of the clients.

Kerry Honan is an Immigration Advocate at HIAS and an AVODAH Corps Member. To learn more about HIAS' work, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.