To Remember and Protect: Yom Ha’Shoah and the Global Refugee Crisis

By Rabbi Rachel Grant Meyer – Educator, Community Engagement

May 04, 2016

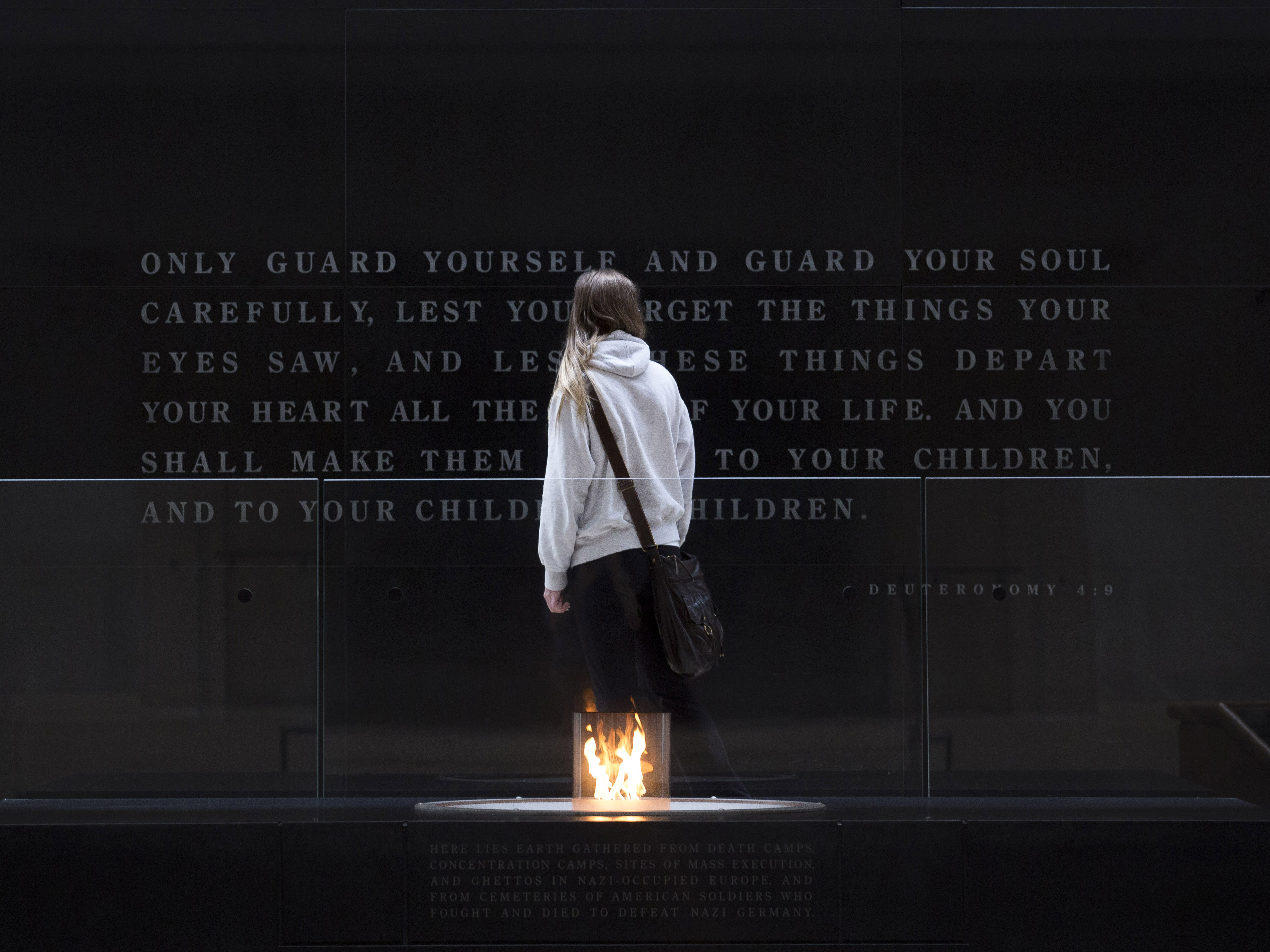

A woman reads an inscription near the eternal flame during the annual Names Reading ceremony to commemorate those who perished in the Holocaust, in the Hall of Remembrance at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, May 2, 2016, in Washington, DC. This year Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom Hashoah) begins in the evening of May 4 and ends in the evening of May 5.

(Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Two years ago, while serving as a congregational rabbi in Manhattan, I accompanied a group of teens from the synagogue youth group to Washington, D.C. for a weekend fieldtrip. As part of the visit, the students had the chance to visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. During our afternoon visit to the Memorial Museum, as I wound my way through the exhibits, I paused to speak with one of the students. As he took in the Memorial Museum, he found himself asking whether it would have a significant enough impact on visitors to truly help them understand just how atrocious and unspeakably evil the Holocaust was. In a hushed voice, he asked me and one of the other rabbis on the trip whether we thought that, when the survivors of the Holocaust are no longer alive, something like this Memorial Museum will adequately do the job of conveying the horrific nature of the Holocaust.

Later, when the group gathered to debrief, I posed this question and some others to the rest of the teens. I asked: will we ever be able to fully convey the gravity of the Holocaust to future generations as the last generation to hear direct testimonial from Holocaust survivors? What are the ways we use memory to convey an experience within Jewish tradition? The teens discussed the parts of the exhibit that had the biggest emotional impact on them. Many of them reflected on the intensity of walking through the room lined with shoes taken from victims of the Nazi concentration camps. They talked about the unique smell of the shoes, about picturing the individual people who once owned those shoes, and about the way in which each pair of shoes brought their owner to life in a way that no text on a wall ever really could.

Together, we talked about the concept of “shamor v’zachor” – to keep and to remember. The Torah teaches us that we are to keep and to remember the Sabbath day in order to make it holy. We spoke about the idea that, in order to keep and remember the Sabbath day, we employ the use of our senses – we kindle the Sabbath lights and watch their glow and feel their warmth; we taste the sweetness of the wine and the delicious challah. I asked the teens whether that same idea might extend to the way in which we think about Holocaust remembrance. Rather than simply making the Holocaust into an academic study – something written about in books or on museum walls – we also have to truly keep it through the use of our senses to put ourselves back into the telling. When we show future generations artifacts from the Holocaust and re-tell the testimony of survivors, it is then that we transcend mere remembrance and also keep the story alive.

That is the Jewish way. When we remember Jewishly we do not simply narrate from a distance, we put ourselves back into the story, utilizing our senses to immerse ourselves in the fullness of an experience so that we can not only remember but also keep it for generations to come. It is the same thing we just did two weeks ago at our Passover Seders. We dipped our herbs in saltwater, tasting the bitterness of slavery. We tasted matzah, the bread of affliction. At the Passover Seder, we do more than simply retell a story about a time long past. We locate ourselves in that narrative and relive the history as though we ourselves had been there, as it says in the Haggadah: “In every generation, everyone is obligated to see themselves as though they personally left Egypt.” We vividly recreate the tale of our exodus from Mitzrayim, from Egypt, from the Narrow Place.

No sooner did we rise from our Passover tables do we find ourselves observing Yom Ha’Shoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day. What does it mean to keep the narrative of the Passover Seder alive – to continue the work of freeing ourselves and others from narrow places – as we also remember the 6 million Jews and millions of LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, Roma, Jehovah’s Witnesses and others who perished in the Holocaust? What does it mean to remember liberation from bondage as we also remember the danger of allowing oppression and persecution to flourish unchecked in the modern world?

Today, we find ourselves in the midst of the worst global refugee crisis since World War II with 60 million people displaced from their homes around the world. Violent conflict and persecution cause 42,500 to leave their homes each day in search of safety. These numbers are staggering. They are not just numbers, though. Each number is a living, breathing person with a story to tell and the potential to be freed from their contemporary bondage.

Keeping the story of Passover alive as we move into the day on which we are told “never to forget” our people’s more recent encounter with unconscionable evil means ensuring that what happened to the Jewish people does not happen to others. We can do this by becoming part of the American Jewish movement in support of refugees. Rather than simply telling their stories or learning about the global refugee crisis as though it is one more story in a museum, we have the ability to get involved right now in the lives of refugees living in our communities and to advocate for the rights of those not yet living in safety. You can volunteer with refugees in your city. You can sign HIAS’ petition against the deportation of Central American refugees. You can give tzedakah to help sustain the lives of refugees worldwide. These are just three ways to take action.

As we pledge “never to forget,” let us also remember the 60 million people around the world who we must remember and protect.