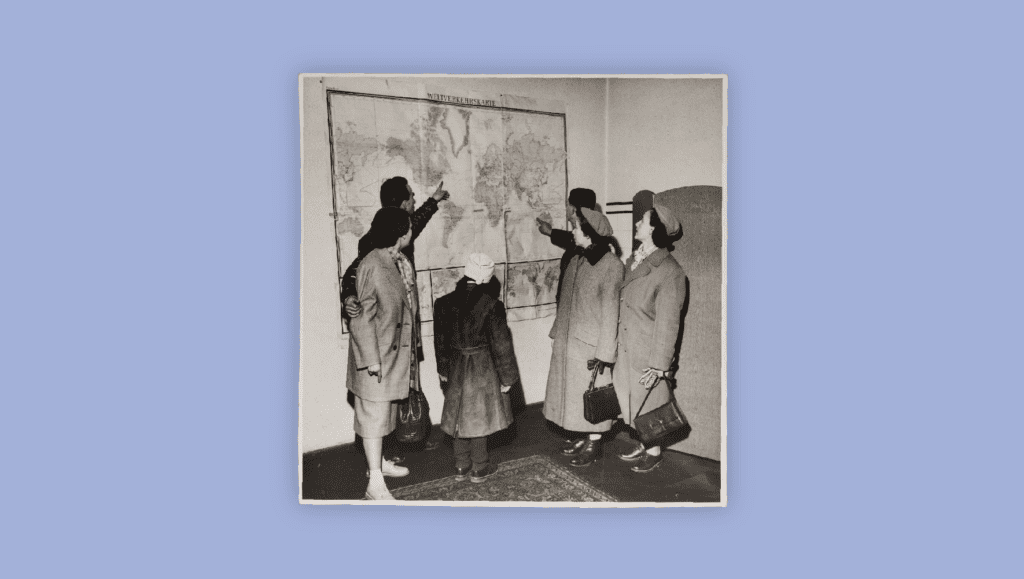

On May 13, 1939, the ocean liner St. Louis set sail from Hamburg, Germany with 907 Jews on board. The passengers were seeking refuge from rising Nazi persecution. The liner was refused entry first in Cuba and then the United States and was ultimately forced to turn back to Europe on June 6. Of those 907 passengers, 254 did not survive the war.

The victims on the St. Louis represent a fraction of the six million souls murdered by the Nazis. But their story cries out for our attention for the role we, as Americans, played. Our leaders, our government, our country – all of us – became complicit in their fate when we turned them away. The memory of the St. Louis challenges the story we tell ourselves about America’s goodness in the face of evil. And it should. We were indifferent. And that indifference enabled evil.

The decision to refuse the ship entry was framed as a pragmatic policy decision at the time. There were calculations about economic and cultural absorption, xenophobic sentiment, and a desire to deter other would-be arrivals. Denying visas was bureaucratic and bloodless. Its air of reasonableness made it palatable to the public. That is often how cruelty is enacted — with a thin veneer of respectable law and order cloaking the most heinous indifference to inhumanity. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, with our moral shortcomings laid bare, a global consensus emerged to make sure our laws would no longer excuse such inaction. The 1951 Refugee Convention laid the groundwork for a world in which the forcibly displaced would not be returned to their persecutors.

Donate today

Today, we again find ourselves in a global crisis of forcible displacement — one that’s twice as large as it was in World War II. 120 million people have fled their homes in search of safety. But the moral clarity of our obligations to refugees and asylum seekers that arose after the Holocaust appears to have worn off.

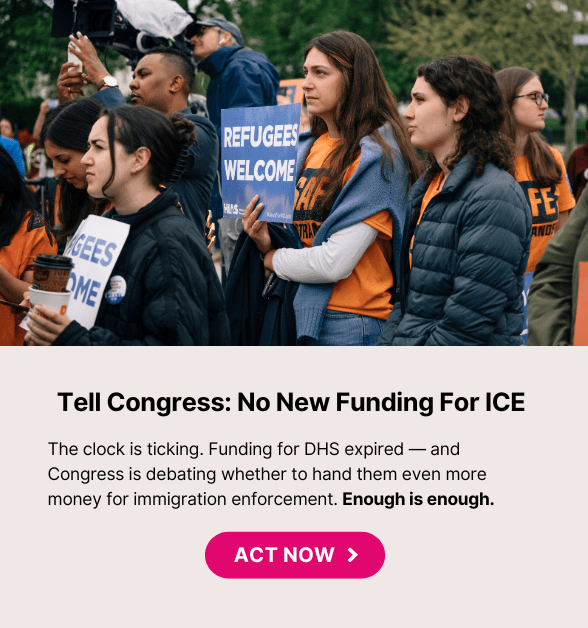

In the United States, we are again guilty of turning people back to the danger they fled. With our borders closed to asylum seekers and the refugee admissions program greatly diminished, we are telling the displaced — those akin to the St. Louis passengers of 86 years ago — that there is no refuge to be found here.

If anything, our behavior today is worse. We are not just using our laws and bureaucracy to cloak an indifference to inhumanity; we are using them to unleash it. We have not only shut down our borders to those seeking refuge, we are swiping it from those to whom it was already promised. We have stripped Afghans and Venezuelans of Temporary Protected Status, making them vulnerable to deportation to regimes we know to be dangerous. We are, almost casually, letting legal statuses for other at-risk populations expire. We have resurrected obscure laws and provisions to bypass due process and send immigrants to detention centers at home and abroad.

In the wake of World War II, we imagined that humanity had moved beyond the shocking cruelty and indifference of that era. We believed that we had learned from our shame over refusing the St. Louis, and that we could safely contain these moral stains in the past. We were wrong. The events we are witnessing now tell us that the St. Louis is as relevant as ever.

We are in a moment when history is calling out to us: warning us not to repeat its worst moments, beseeching us to choose differently. It reminds us that we too will have to face our own place in its annals. May what we ultimately write in its pages be a source not of shame for our inaction — but of inspiration for how we summoned the courage to change course.