Stranded in Mexico: The Human Cost of Title 42

By Ayelet Parness

HIAS.org

May 18, 2022

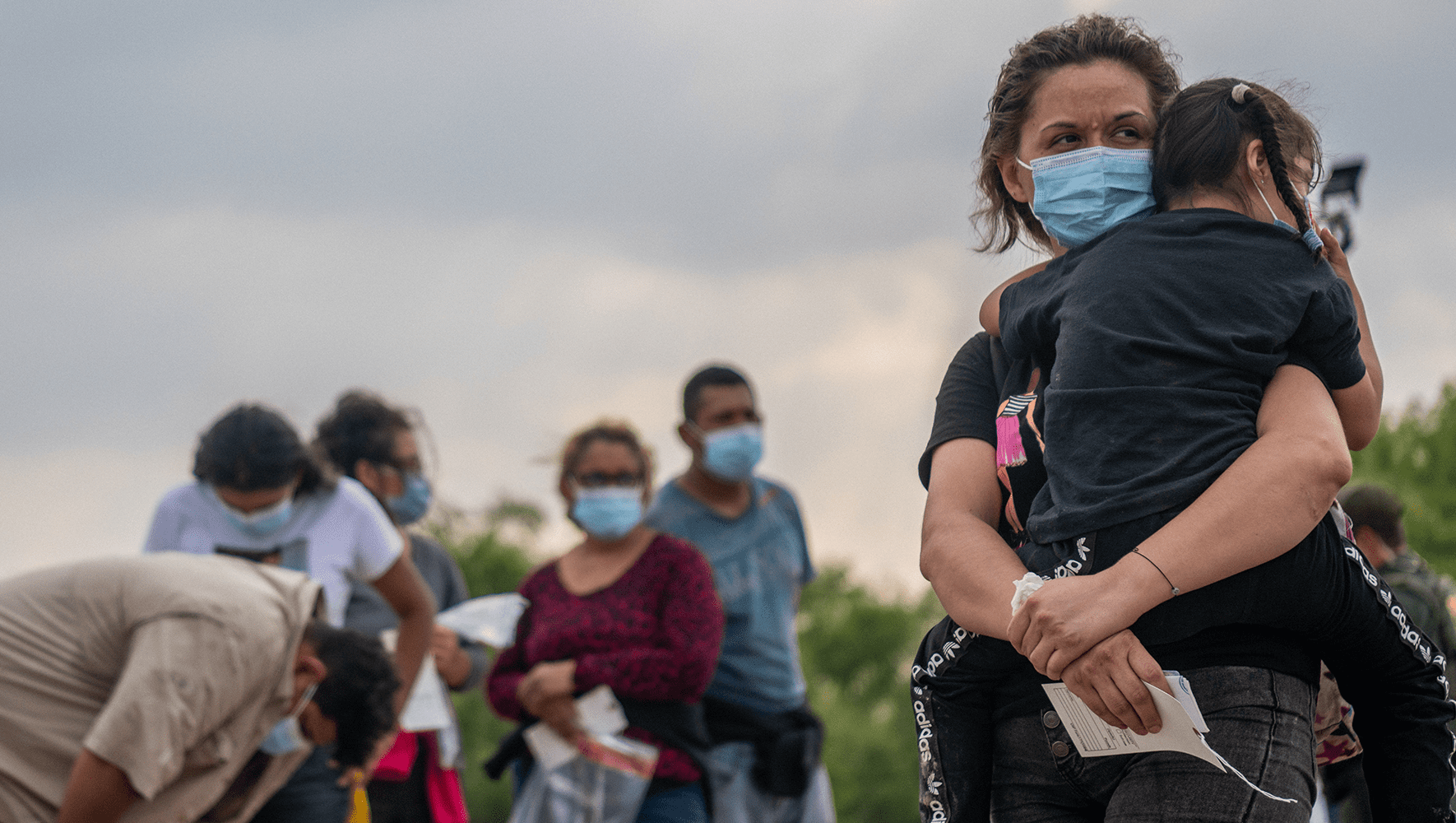

El Salvadorian migrants Yesenia Martinez and her daughter Jaretzy wait alongside other migrants to be processed after crossing the Rio Grande into the U.S. on May 03, 2022 in La Joya, Texas. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

Before August 2021, Ana* had never even considered leaving her home in Hidalgo, Mexico. Then she was kidnapped by members of a drug cartel, and discovered that the father of her children – who had abused her – was in league with her kidnappers.

After her captors released her under the promise that she would return to work for the cartel, she fled north with her children to Juárez, a city just across the border from El Paso, Texas. At each stage of her journey, she was terrified that her kidnappers were on her heels. Yet when she presented herself to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) at a port of entry, she was prevented from seeking asylum – a right guaranteed by U.S. and International law.

“They told me there was no way I could cross into the United States,” said Ana. “Even if my life was at risk, they didn’t care.”

Since March 2020, a public health law known as Title 42 has blocked people from seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border, ostensibly to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Although public health experts have stated from the start that the policy does not improve public health and other entry restrictions have long ago been lifted, as of March 2022 there have been over 1.8 million expulsions under Title 42.

On April 1, 2022, the CDC announced that the Title 42 order would end on May 23. Since then, numerous legal and legislative challenges have been raised to prevent the policy’s end, with pressure to continue Title 42 coming from both sides of the political aisle as midterm elections approach. Those lobbying to preserve this health order cite fears that ending Title 42 will lead to more people attempting to enter the U.S., despite the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) outlining a robust strategy to manage arrivals at the border.

Update: On May 20, 2022, U.S. District Judge Robert R. Summerhays in Louisiana issued a preliminary injunction preventing the federal government from ending Title 42. Our statement on this ruling can be found here.

The human cost of continuing to enforce this policy is high; for over two years, people denied entry under Title 42 have been forced into some of the most dangerous areas of Mexico, where they are frequently targeted for violence. Since President Biden took office, Human Rights First has tracked at least 9,886 cases of kidnapping, torture, rape, and other violent crimes against those impacted by Title 42.

“Asylum seekers and migrants are targets of violence because everything they have is on their back,” said Nicolas Palazzo, a HIAS border fellow working for Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, an El Paso-based nonprofit providing free and low-cost legal services to immigrants and refugees. Currently, six HIAS border fellows work at nonprofit legal organizations in the border regions of Texas, Arizona, and California to increase their capacity to provide legal representation to asylum seekers.

“People know that law enforcement will not protect migrants,” continued Palazzo. “I have yet to see a single investigation of violence against one of my clients completed.”

Staying at a shelter in Juárez, Ana felt unsafe, unsupported, and alone. Her children were often sick, and she had to leave them at the shelter while she worked. They did not have much money or food, and the area where they lived was so dangerous that they rarely went outside. On top of the prevalence of violence and kidnappings in her area, her children’s father had called to threaten her.

“He told me that he knew that I was already at the border, and that when I least expected it, he was going to be there,” said Ana. “All of that was always on my mind, and I was very afraid.”

One day, she was robbed and threatened with further violence while picking up a money order at a local convenience store. Rattled by the experience, Ana felt so desperate and unsafe that she considered sending her children to cross alone into the U.S. She hoped that, as unaccompanied minors, they would not be turned away.

Like Ana, James** brought his family to the U.S.-Mexico border in search of refuge but instead found only danger and violence. As a Black Haitian, though, James also experienced an intense degree of discrimination during his time in Juárez. In the streets, he was regularly physically attacked, shouted at, told to return home, and called anti-Black slurs.

Persecuted for his political beliefs in his home country and with no legal options at his disposal, James decided to cross into the U.S. between ports of entry with his wife and three-year-old child. The family was caught by the border patrol, who sent them to detention overnight and then expelled them all the way back to Haiti, handcuffed at the wrists and feet. Thanks to Title 42, James and his family were delivered back to death threats without even the chance to make their case.

“When we arrived in Haiti, I was sleeping under the bed because the people [who threatened me] have taken control of the country,” James told me. “I could not stay in Haiti.”

Despite their terrible treatment in Mexico, the family returned rather than risk remaining in Haiti. But back in Juárez, James says the family’s landlord arranged to have them attacked by a group of people – an attack he believes was motivated by anti-Haitian discrimination. The men robbed the family and beat and threw tear gas at James, injuring him and his child. The landlord has since evicted them and refused to return their security deposit.

“About 70% of the people that call us [at Las Americas] are Haitian,” said Palazzo. “They’re incredibly vulnerable because of everything else that people are suffering – violence, medical issues – but then there’s the aspect of rampant discrimination and racism. “

Ana and James are fortunate to have one more thing in common – both contacted Las Americas, where Palazzo and his colleagues took their cases. Since September 2021, his team has worked to exempt over 1,000 asylum seekers from Title 42, most of whom have severe medical conditions or have faced harm in Mexico.

While the program has been very successful, Palazzo calls this number a “drop in the bucket”; very few asylum seekers are even able to access legal help from Mexico, even if they meet criteria for exemption.

After 8 months living in Juárez, Ana and her children were some of the lucky few exempted from Title 42 and escorted across the border on April 23. And on the call with James, Palazzo delivered some exciting news – the family had tested negative for COVID-19, and would be allowed to cross into the U.S. the next day.

“I’m hoping that my life will change, my wife’s life will change, and my child’s life will change,” said James. “I know that my life will change, because I will feel safe.”

In the U.S., both Ana’s and James’s families will face a difficult battle – a slew of court hearings to determine whether their asylum requests will be accepted.

“They are placed in Title 8 proceedings – the customary route for those seeking asylum in the United States,” said Palazzo. “What people don’t understand is that the elimination of Title 42 does not mean that suddenly, anyone can enter the United States and remain forever. They still have to appear in court before an immigration judge or an asylum officer and argue their case. The end of Title 42 gives asylum seekers the opportunity or the right to seek asylum.”

In spite of this, Ana is relieved to be in her new home in Chicago.

“Everything has changed for me,” she said. “My children are enrolled in school. We go to the park with no care in the world. We’re happy. We’re stable. We’re living a peaceful and secure life.”

Want to take action? Ask Congress to stand for asylum and vote no on keeping Title 42 in place

*Pseudonym used for client’s protection.

**James is identified by first name only for his protection.