Going Deep Into the Guyana Forest to Help Refugees

By Sharon Samber, HIAS.org

Jan 08, 2021

In late fall of 2020, Alex Theran found herself trekking in the rain through the jungle of Guyana, walking on logs to stay out of the mud.

Theran is the new country director of HIAS Guyana, and the office only opened last year. The country is a relatively new destination for refugees, but the displaced population there has grown rapidly. About 22,000 Venezuelans — more than half of them women — live in Guyana, joined by Guyanese citizens who lived in Venezuela but fled, and the country is also home to the Warao indigenous community.

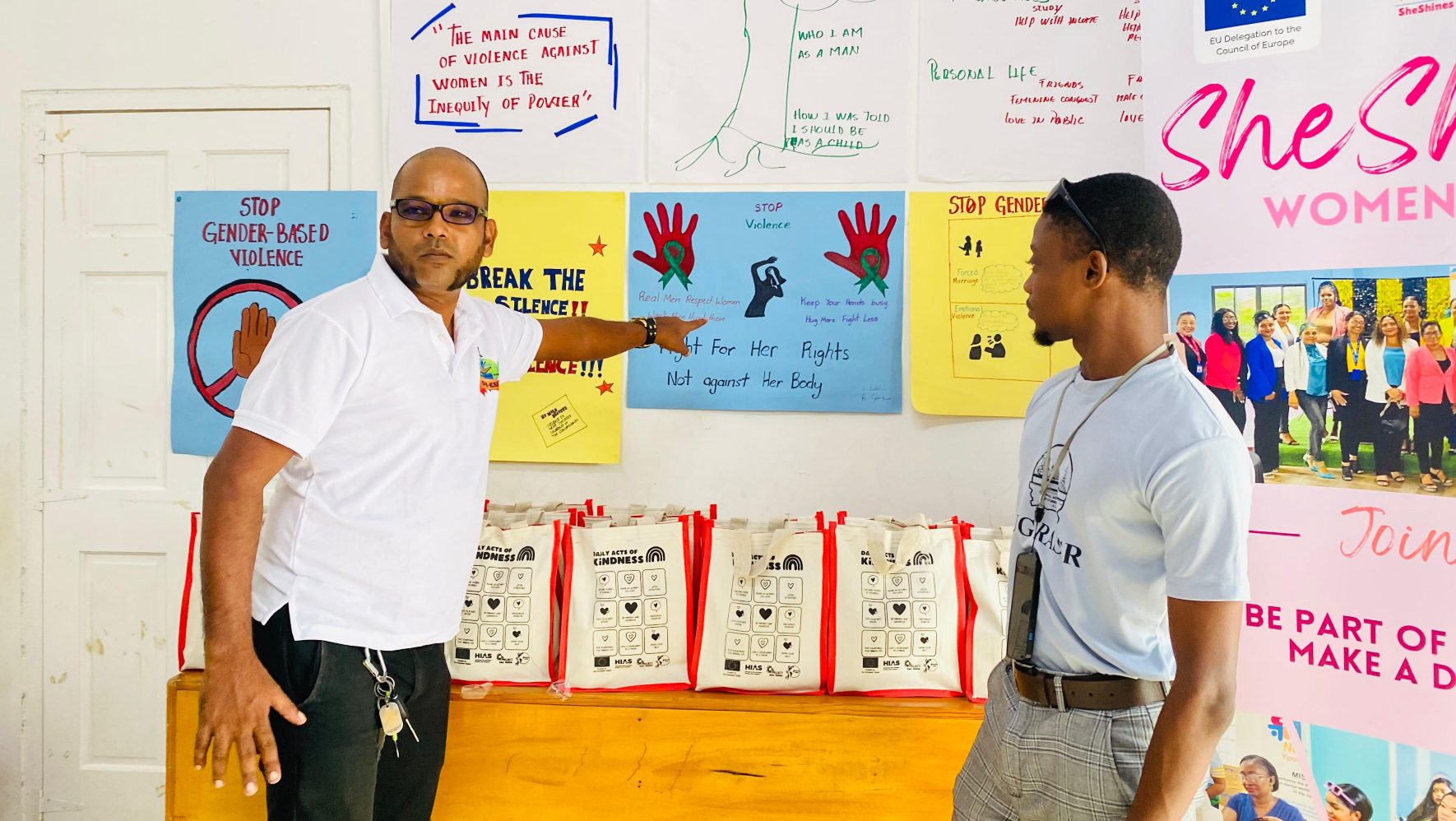

Theran set up offices in the cities of Bartica and Georgetown to address a number of issues: human trafficking and the sexual exploitation of women and girls; gender-based violence; lack of basic services; and,of course, the ramifications of COVID-19. But doing all of this in a pandemic, and in a new country where HIAS is little-known, was a challenge. Theran and her staff realized they needed to go into the field to find more people they wanted to help, and that’s how they found themselves walking on log paths to get to villages outside of Port Kaituma.

Port Kaituma, a village of 4,000, is located near the Guyana-Venezuela border on a river deep in the jungle. Mines in the area have always attracted foreign labor from Venezuela and Brazil, Theran explained, but many Venezuelans now want to stay in Guyana. There are currently about 300 recently arrived Venezuelans in the Port Kaituma areas, and that number is rising.

When Theran and Andrea Ortiz, programs manager at HIAS Guyana, visited to conduct a needs assessment, they were surprised by the remoteness of the area and the poor conditions.

“I've lived in extremely remote places, but I was in disbelief,” Theran recalled. A number of people they saw appeared malnourished and some hadn’t had any medical attention in several years. “The needs are fairly significant,” Theran said.

Based on the HIAS assessment, UNHCR, the U.N. refugee agency, will provide funds to place a HIAS case manager in Port Kaituma. Future plans may be harder and more expensive to put in motion. Theran would like to supply the community with information technology, set up English classes, and hire Spanish translators. HIAS also wants to introduce community resources like a tool library, which would help people construct their own dwellings or be able to farm. One bright spot is that the local communities are mostly happy to have the refugees in their villages and willing to integrate them.

As the pandemic continues, the formal entry points into Guyana remain closed and permits to stay in the country are not being issued. Venezuelans need more information about their rights in Guyana and access to education and mental health services. But Theran is hopeful and determined.

“We are willing to go wherever the people are, regardless of the challenges,” she said.