Laura Medvedieva vividly remembers her harrowing journey from Kyiv in the days following the Russian invasion. “Nobody believed the war would really happen,” she said. “One day everything was normal and I was out painting with my friends. The next day we were forced to pack up and leave our home.”

Medvedieva, a professional landscape and still–life artist, drove from Ukraine’s capital with her husband Sergei, a jeweller, their 12–year–old son Artiom, and their golden retriever, Rix. They headed for Lviv, a city in the west of the country, for what they thought would be a short stay before they returned home.

“We only packed for a few days,” she recalled. “We had one bag for food, one bag for dog food and one bag for art supplies. We were on the road by the time we realized we wouldn’t be returning home soon. We drove through traffic jams for two days just to get to Rivne [205 miles west of Kyiv] and, after 48 hours without sleep, pulled over for a nap. After 15 minutes we were woken up by a loud noise. The Russians had bombed Rivne airport.”

Things weren’t any better in Lviv. “The military sirens were going off all the time. We knew we had to get out so we drove on to the Polish border. Along the way I counted 23 explosions.”

Although Sergei, like all Ukrainian men of military age, was barred from leaving the country, a charitable group in Poland agreed to buy airline tickets for Laura and Artiom. Rix was also brought to safety. “We used to bring Rix to help with children with special needs so he is a trained as a support dog. When we explained this to the airline they agreed to let him fly. It was a miracle.”

There was still one major question: Where should they go? “A friend of ours had worked in Ireland and said it was a lovely place, so we decided to go to Ireland.” In her desperation to find safety, though, Laura had confused “Ireland” with “Iceland” in her thoughts. Even as the plane began to descend, she thought they were going to the isolated Scandinavian island.

Although Medvedieva fell in love with Ireland immediately, her initial experiences were marred by a failure to secure medium-term housing. Over the next two months she would learn that many apartments had a no-pet policy and that her decision to save their beloved golden retriever had hampered her ability to find a safe home for her family. With no alternative she contacted everybody she knew herself and then, after that, everybody her friends knew. One of those desperate messages arrived at the offices of the Jewish Representative Council of Ireland (JRCI).

The JRCI was already in pandemic crisis mode when the war in Ukraine broke out but, like so many Jewish organizations across the world, it immediately switched its focus to helping refugees. So far the representative body for the community of 3,000 Jewish people in Ireland has assisted 22 Ukrainian families who have come into the country.

“About half of the people we are helping were in Ireland already and the other half were looking to get to Ireland,” said Saul Woolfson, an experienced immigration lawyer and director of the JRCI Ukraine Welcome Programme. “The people we help are not necessarily Jewish. Some, like Medvedieva, are married to a person of the Jewish faith but many of the refugees just happened to be referred to us by another Jewish organization. We don’t turn anybody away. Gone are the days when we only helped people because they were Jewish. Now we help people because we are Jewish.”

The JRCI’s efforts to support refugees fleeing to Ireland are supported and largely funded by HIAS and its approach mirrors the “Welcome Circle” strategy piloted by HIAS in the U.S. Through Welcome Circles, a group of 5-8 volunteers provide their new neighbors with the type of assistance usually provided by resettlement professionals for a period of around six months, often with support from their broader community.

The JRCI has established an Irish Welcome Circle of 10 people to provide a wide range of support for the refugees they assist. This circle includes a native Ukrainian speaker to interpret, a qualified psychotherapist to help with the traumatic dislocation, a local entrepreneur who can help refugees find meaningful employment and Judy Czerniak — whose role as a dedicated Community Integration Officer is funded by HIAS.

“Our core principles center on providing assistance in the most sustainable way possible,” said Woolfson. “We transition people to independence as soon as possible. This means own–door accommodation, jobs, learning English and integrating into the local community.”

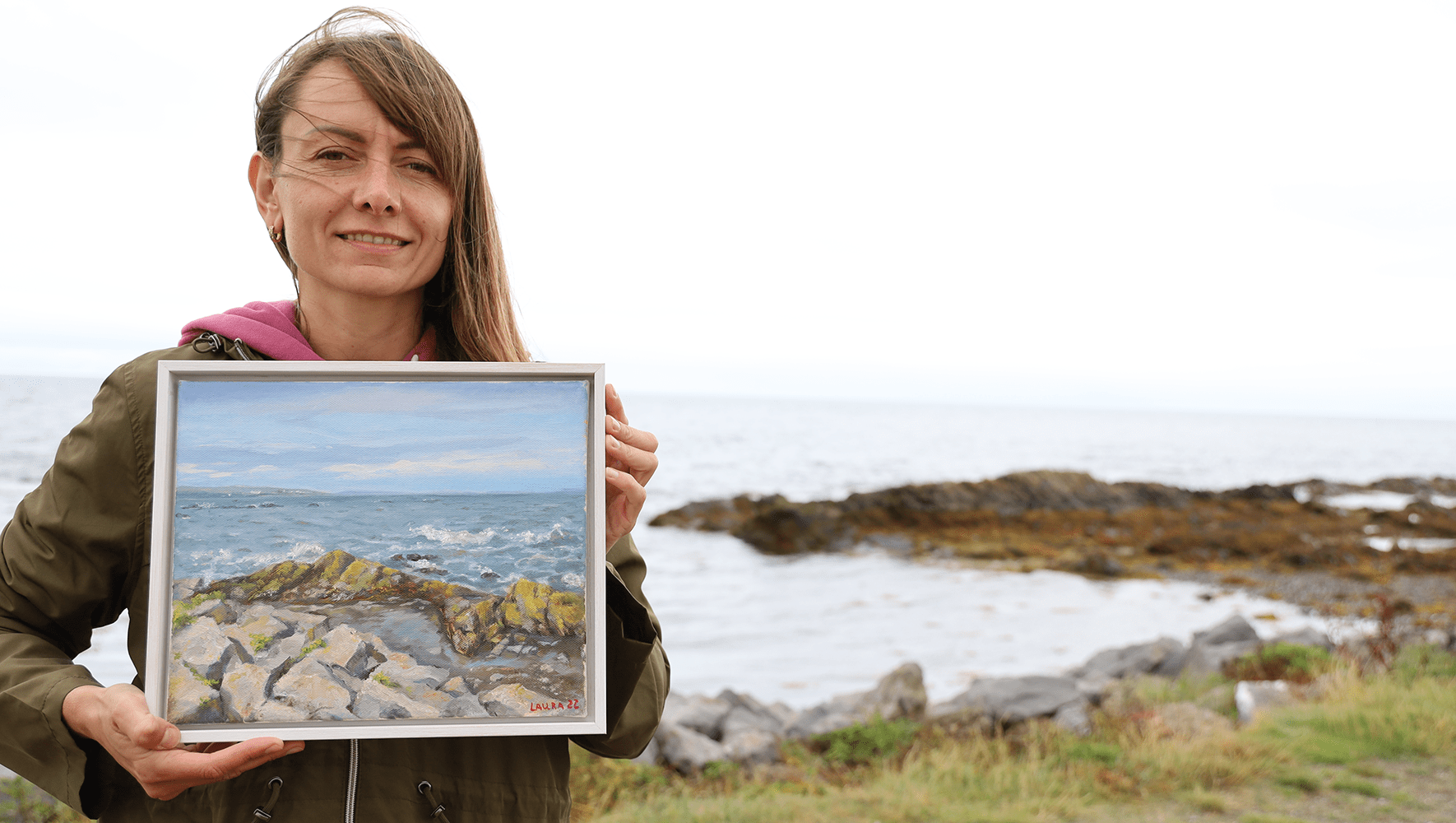

After the Irish media highlighted Medvedieva’s plight, she found accommodation in North Dublin, in a beautiful cottage with a separate artist’s studio, where she works with supplies provided by the JRCI. Artiom is enrolled in the local school and, according to Laura, even Rix is happy with their new surroundings.

Medvedieva said: “I am more than happy. I am very happy. They [the JRCI] have made me believe that I can be a professional artist in Ireland. I love Ireland. I never want to leave.”

“We’re delighted that the JRCI could help settle almost 50 Ukrainian refugees, from all over the country,” said Katharine Woolrych, the advocacy officer of HIAS Europe. “From Kyiv to Kharkiv and beyond, they’ve been given a warm welcome by the Irish.”

Tatania Teslyeva is an interior designer from Kharkiv, a city 290 miles east of Kyiv and only 50 miles from the Russian border. Since the war broke out in February, Kharkiv has been the scene of some of the deadliest fighting. Teslyeva’s family initially moved to a property they owned in the countryside before the encroaching warfront forced them to relocate to neighboring Moldova, where Tania’s aunt is the director of the Jewish Cultural Centre.

Over half a million Ukrainian refugees have sought shelter in Moldova to the west of southern Ukraine. One of Europe’s poorest and smallest countries, Moldova only has a population of only 2.6 million people and can offer only limited resources to those seeking shelter or work. After a few months volunteering with her aunt in the center, Teslyeva wanted to find somewhere she could get a job that would allow her to look after her extended family.

Now settled in rural Kerry, Ireland, Tania Teslyeva watches as her seamstress mother Natalia uses the sewing machine provided for her by the Jewish Representative Council of Ireland (JRCI), August 29, 2022. (Tom McEnaney for HIAS)

Teslyeva’s husband, Andrey, is a merchant seaman who had been impressed during his time docked in Cork, which is why Ireland’s second–largest city became their destination of choice. So, Tania and Andrey packed up their car for the third time, to make the 1,900-mile journey to Ireland.

“We had enough money for six months and I was sure I could find a job, as an interior designer, as a painter, or working in a supermarket; whatever. I drove across six countries, Moldova, Hungary, Austria, Germany and France,” Tania said. “The problem was accommodation. We had money but it is very difficult to get somebody to rent to you when you are a refugee with no job and no papers.”

The JRCI put Teslyeva in touch with Sophia Spiegel, the JRCI Welcome Circle member based in the south of the country. Sophia moved the family into her own home for two weeks while she sourced suitable accommodation, which turned out to be a farmhouse in rural Kerry. “Sophia is our best friend in Ireland,” said Teslyeva.

JRCI helped to furnish what was a largely unfurnished property, so that Teslyeva could invite her mother Natalia and her father Ihor to join her in the safety of rural Ireland.

Teslyeva is sitting at the dining table of her new home as she describes her new life in Ireland. Seated beside her is her mother, a seamstress with 40 years’ experience, who spends the entire time polishing her new sewing machine, provided by the JRCI, with undisguised pride.

“Just after we moved in the neighbours came up to us and said: ‘Anything you need, just ask.’ Teslyeva said. “We are happy here, or as happy as we can be given what is still going on in Ukraine.”